SOMETHING remarkable happened to May McLean at the Mitchell Library last April.

She was in the audience for a talk at Aye Write! by Tessa Dunlop, author of a book about the women who had served at the top-secret Bletchley Park, which housed the crucial British code-breaking operation during the war against Hitler. This was where the Nazi cipher system, Enigma, was famously broken.

The author was delighted to find that her audience included three 'Bletchley girls', all in their 90s, and invited them on stage for a question-and-answer session. One of them was May who, like all the others, had never spoken of her war-time service.

Asked when she had begun her decoding work, she smiled: "They told us to forget everything and I seem to have succeeded!"

Then the largely female audience rose as one and gave the trio a standing ovation. Afterwards, dozens of them crowded forward to shake their hands.

For a woman who had spent 65 years avoiding the subject of what she had done during the war, it was a surreal experience.

May's story now features in a new book about the history of Erskine, where she has lived since April 2010.

May was born in September 1922 in her grandparents' home in the Ibrox area. She was educated at Scotland Street School and at Govan High School.

She remembers feeling "awful" when war broke out in September 1939. In 1941, an air-raid siren caused by the Luftwaffe showing up over Glasgow saw her and her friend Dora being shepherded into the Savoy Cinema.

"Afterwards it took ages to get home because the trams were off," she recalls. "We found my mother and father and their friends had spent the evening sheltering under the dining table."

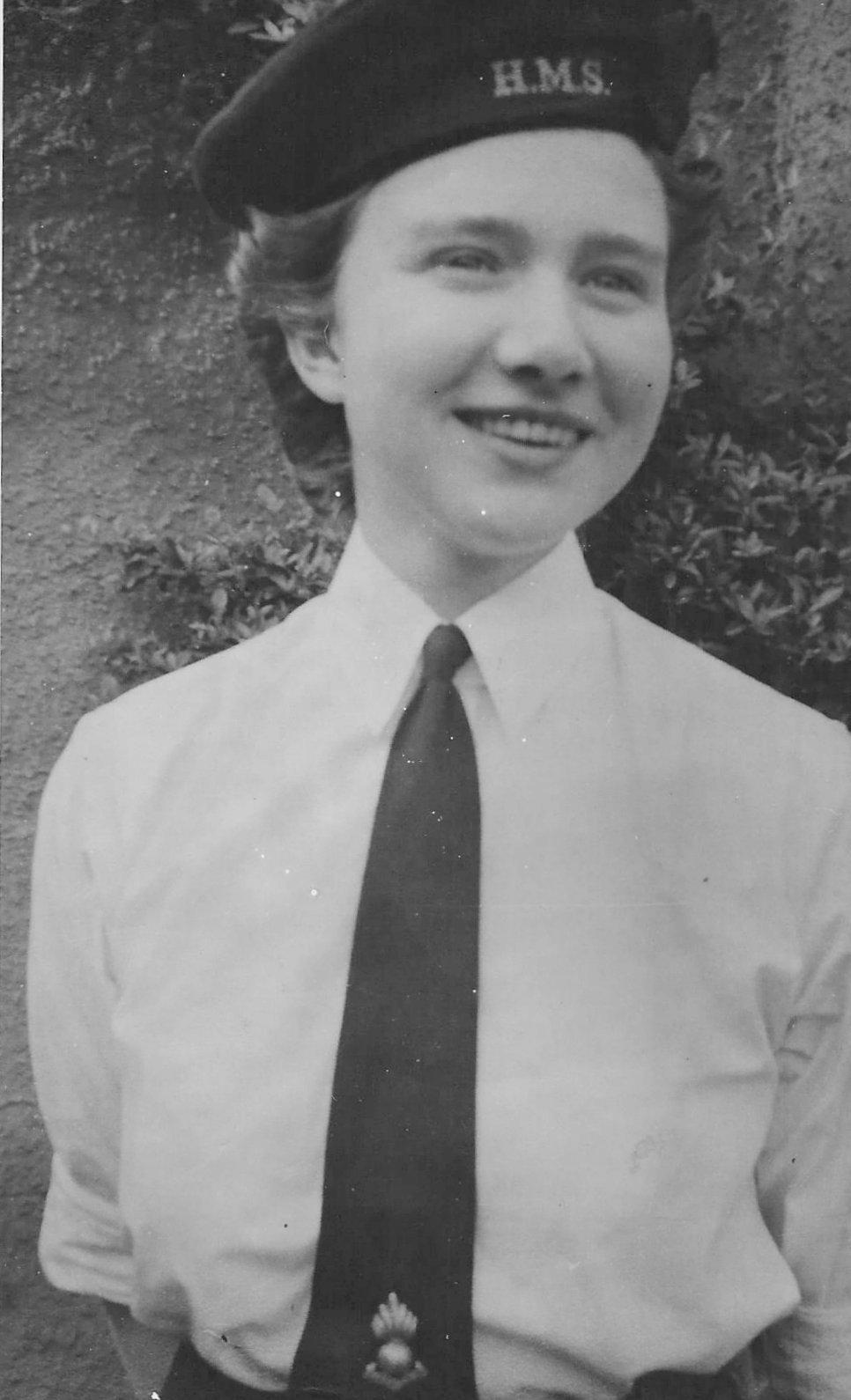

May joined the Wrens - the Women's Royal Naval Service - and when she was interviewed at a Glasgow hotel she was asked if she was interested in doing 'secret work'.

"We were told not to go blabbing about this to anyone, even our parents," she said. "I was sent to Leeds for training, where there were lots of tests. They wanted to see if we were suitable and weren't flibbertigibbets!"

In late 1943 she was allocated to Stanmore, in North London, one of the outstations that served Bletchley Park. For the rest of the war she worked one of the many Bombe machines that Alan Turing and his fellow cryptanalyst, Gordon Welchman, had developed in 1941 to crack the Enigma code used by the Germans to send top-secret military reports and instructions.

With the Germans changing the code every 24 hours, cracking it became a daily race against time, with thousands of lives potentially hanging on success or failure.

"The machines were huge, as big as wardrobes," says May. "You had to stand on something to reach the top. They were full of wires and had rows of coloured discs on the front."

May's task was to take down 'cribs' - fragments of probable text, worked out by the decoders at Bletchley - and set up the Bombes to test them by performing a chain of logical deductions.

"We'd enter the letters and the numbers and then set up the machine going. It made a 'bumpity bump' sort of noise and when it stopped, we'd take down the letters and send them off. You were just a tiny cog in a big machine. You got bits of things that made sense when they were put together but it didn't mean a blooming thing to us."

May concluded that they were handling messages to and from German U-boats.

Her war did not end with VE Day in May 1945 - she found herself one a group of young women from Stanmore chosen to do decrypt work on Japanese codes in Ceylon (now Sir Lanka). But then the bomb fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki - and the Japanese surrendered.

Asked if she was proud of her war work, she said: "Proud? I never ever thought about it. I just got on with the job in front of me and hoped I was doing it to the best of my ability.

"We couldn't say anything for decades, by which time we had forgotten about most of it. Nobody ever mentioned Bletchley Park and I have still never been there. During the war I'd never heard of Alan Turing or the Enigma code."

She remembers being astonished when told that the work done at Bletchley Park and its out-stations may have shortened the war by at least two years.

* A Century of Care: Erskine 1916-2016, by Anne Johnstone, Jennifer Cunningham and Russell Leadbetter, is published by Erskine (£12)

AT a public meeting held in Glasgow City Chambers on March 29, 1916, a proposal to establish a hospital in the West of Scotland for amputees wounded in battle was approved. Such was the overwhelming public support for the Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers, as it was named, that £100,000 was contributed within a few weeks and doubled within the year. Today the charity, now known as Erskine, needs to raise over £8.5million a year to continue the work started in 1916.

To mark this momentous day in Erskine’s history, the Provost of Renfrewshire and the Chairman of Erskine are hosting a Civic Reception in Paisley Town Hall this evening. Guests will hear how the hospital was established and be able to see some of the original documents including the admissions book from 1916.

Speaking ahead of tonight's Civic Reception, Lieutenant Colonel Steve Conway, Erskine Chief Executive, said: “This evening marks the start of our centenary events which also include a Service of Commemoration in Glasgow Cathedral, Open Days, and the Erskine Ball, which this year returns to Mar Hall where the hospital was founded.

"I think it is fitting that this year we pay tribute to all those staff and volunteers who have cared for over 85,000 veterans to such a very high standard, and also thank all our supporters, past and present, that enable us to continue our work. I hope as many people as possible will be able to join us at our events to learn a little more about our history and join us in our celebrations.”

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here