THE tenth anniversary of Scotland’s Festival of Museums promises a taste of Japan in Kirkintilloch, a look back at hair-raising medical treatments of old at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons and some jiggin’ on the riggin’ at the Tall Ship ceilidh.

But in Govan, all eyes will be on Rents, Rivets and Rotten Tatties, a fascinating exhibition all about the role the area’s women played in the shipyards during the First World War.

ANN FOTHERINGHAM got a sneak preview.

AT the heart of Fairfield Heritage’s exhibition all about women workers during World War One, lies the story of Jeanie Riley.

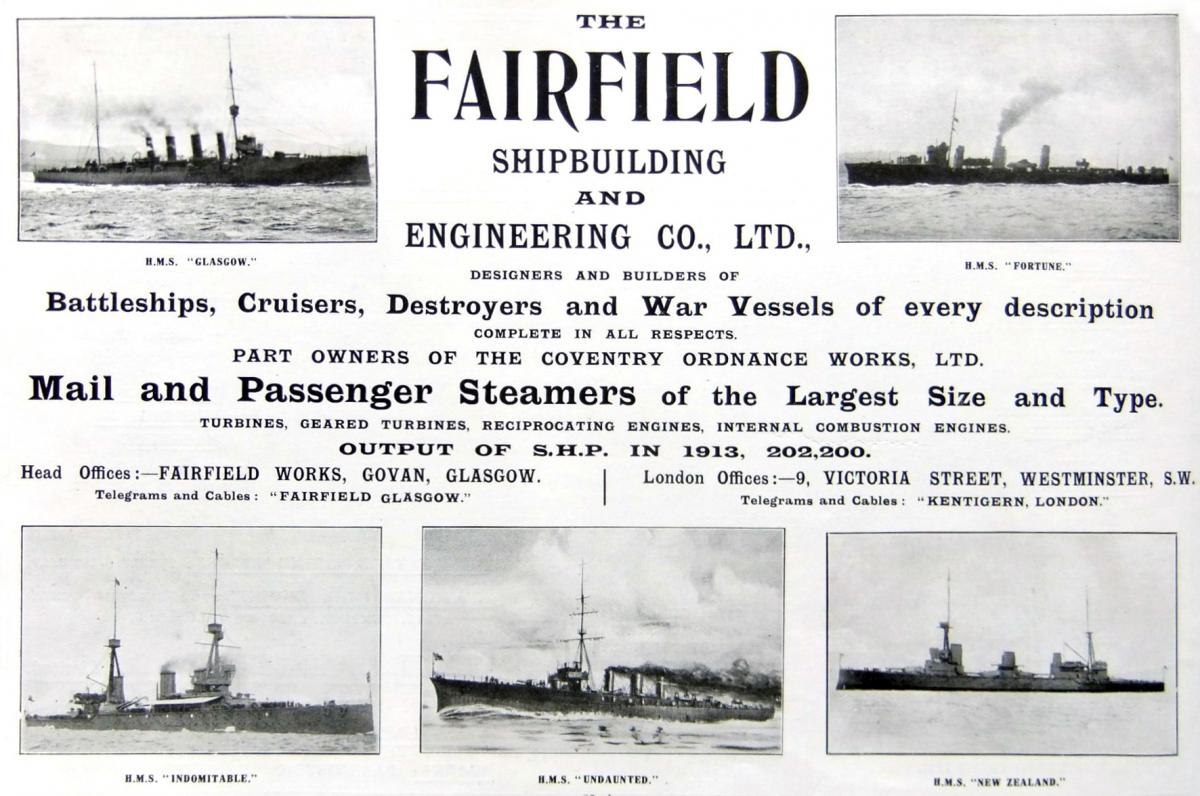

When she was 23 years old, with two young children, Jeanie became a munitions worker in the engineering shops at Fairfield, the Clyde’s biggest yard, responsible for luxurious ocean liners, steamers and warships.

She wrote regularly to her husband James, a Private in the Scottish Rifles, and her letters, lovingly preserved by the Riley family, provide a moving and fascinating insight into the life of a female shipyard worker.

Curator Abigail Morris explains: “Jeanie’s story is part of our exhibition all about the role women played during World War One here in Govan.

“Before the war, women had traditional roles, in the home.

“Of those who did work, around half were in domestic service and the rest worked in clothing factories, or food, drink and tobacco industries - and married women were expected not to work at all."

She adds: “But when war broke out, and it was obvious it wasn’t going to be over soon, women had to fill the vacancies left by men.

“We wanted to tell their stories – lots of people know the story of Mary Barbour, who stood up against the landlords imposing huge rent increases in Govan, where they knew demand was highest and people were desperate.

“We wanted to tell the stories of the other women in Govan, who joined the shipyards and contributed to the war effort."

Jeanie’s letters, which are included in the exhibition, show how excited – and sometimes fearful - she was in her new job.

“Dear Jamie, I am still sticking in at my work - I will be an engineer before long,” she wrote.

“There are 25 more women coming in on Monday and we were told that the amount of work we do in three weeks would have taken the men three years, and Jamie, the men are quite mad at us.

“We all got our photo taken at the launch a week on Saturday and then we saw the ship getting launched and it was lovely. I never saw the like of it before.

“The woman I went up for in the morning, her name is Murphy…well, she lost her finger in the work tonight. She saw it lying on her machine, they tried to tell her it was not off but she would not take it in …if I am offered a machine I will refuse it, for I see enough.”

It’s also clear how concerned she was for her husband’s safety.

“Dear Jamie, I feel glad to hear that you are out of the trenches for a rest as no doubt you must be needing one for they must be worse than awful out there,” she wrote.

In fact, Jamie had survived a brush with death when a bullet hit him just above his heart. The bullet was stopped in its tracks by a small, metal mirror he had picked up as a souvenir from the battlefield, along with a German drill book, which he had put in his tunic pocket. The bullet had pierced the book, but had been stopped by the metal case, and unsurprisingly, he kept the dented mirror for the rest of his life.

The letters also reveal how hard it was for Jeanie, like most Govan women, to cope with the increased cost of living. Even with her munitions wages and separation allowance, prices were going up, and it was hard as all left-over money went on postal orders and parcels to send to their husbands.

In 1912, 80 per cent of a working class family’s budget in Glasgow was spent on rent for accommodation that was often substandard, and basic food.

“Dear Jamie I am sorry I could not send any more, messages are getting so dear here that it takes us all our time to buy them,” she wrote. “They are getting dearer every week. I don’t know how the poor people will like it if it gets much dearer.”

Jeanie left Fairfield at the end of 1916 after becoming pregnant with her third child. James was demobilised in 1919 and found work as a labourer in a brewery then in the council’s parks department. The couple had four more children and of their six, they lost two – the oldest, Mary, who died in 1915 from scarlet fever, and Patrick who died in 1918.

Jeanie and James stayed in Glasgow for the rest of their lives – Jamie died in 1968 aged 78 and Jeanie died 1979 aged 86.

“Jeanie’s letters are really interesting because they reveal what it was like for a woman to come into the environment of the shipyards,” explains Abigail.

“It was dangerous and difficult work, but women were confined mainly to the workshops rather than getting the chance to work on the ships.”

The type of work women did varied from yard to yard, but generally they were given bench tasks, such as fitting, filing, chiselling and marking-off, or machine tasks, such as drilling, tapping, boring, milling and turning-lathes.

The number of women in industry increased by more than a million during World War One, as the government fought to fill the vacancies left by men, in a bid to create a strong war-based economy. The sharpest rise was in metal and engineering trades, from 170,000 to 594,000.

Exact figures for the number of women employed at Fairfield are unknown, but it is estimated to be between 495 and 891 at any given time. Nationally, around 31,000 women were employed in the shipbuilding industry – around 6.6 per cent of the workforce.

The normal working week for a woman was the same as a man – 54 hours – and because wage rates were governed by Statutory Orders, women should have been paid the same as men for doing the same jobs. But in reality, that was not the case.

In general, shipyard owners were reluctant to expose women to construction work, viewing them as temporary workers and giving them only basic training.

It wasn’t all bad though – the exhibition reveals that shipyard owners did invest in extra facilities for their new women employees, such as toilets, cloakrooms and canteens. In fact, the shipyard canteen was an innovation created because of women workers – although it also had the added bonus of keeping the male workers out of the pub at lunchtimes….

Find out more at Fairfield Heritage on Govan Road, this weekend, or visit www.fairfieldgovan.co.uk The Festival of Museums, a weekend long celebration of Scotland’s culture, runs from May 13 to 15. For the full programme visit www.festivalofmuseums.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel