FROM gangly, wild-haired teenager to one of Britain’s great sporting heroes, Sir Andy Murray may have been forced to hang up his rackets but his impact will be felt for generations.

Not since the 1930s had Britain been able to celebrate a male tennis champion until Murray, both ordinary and extraordinary, battled his way to the top of the sport in an era of unprecedented strength.

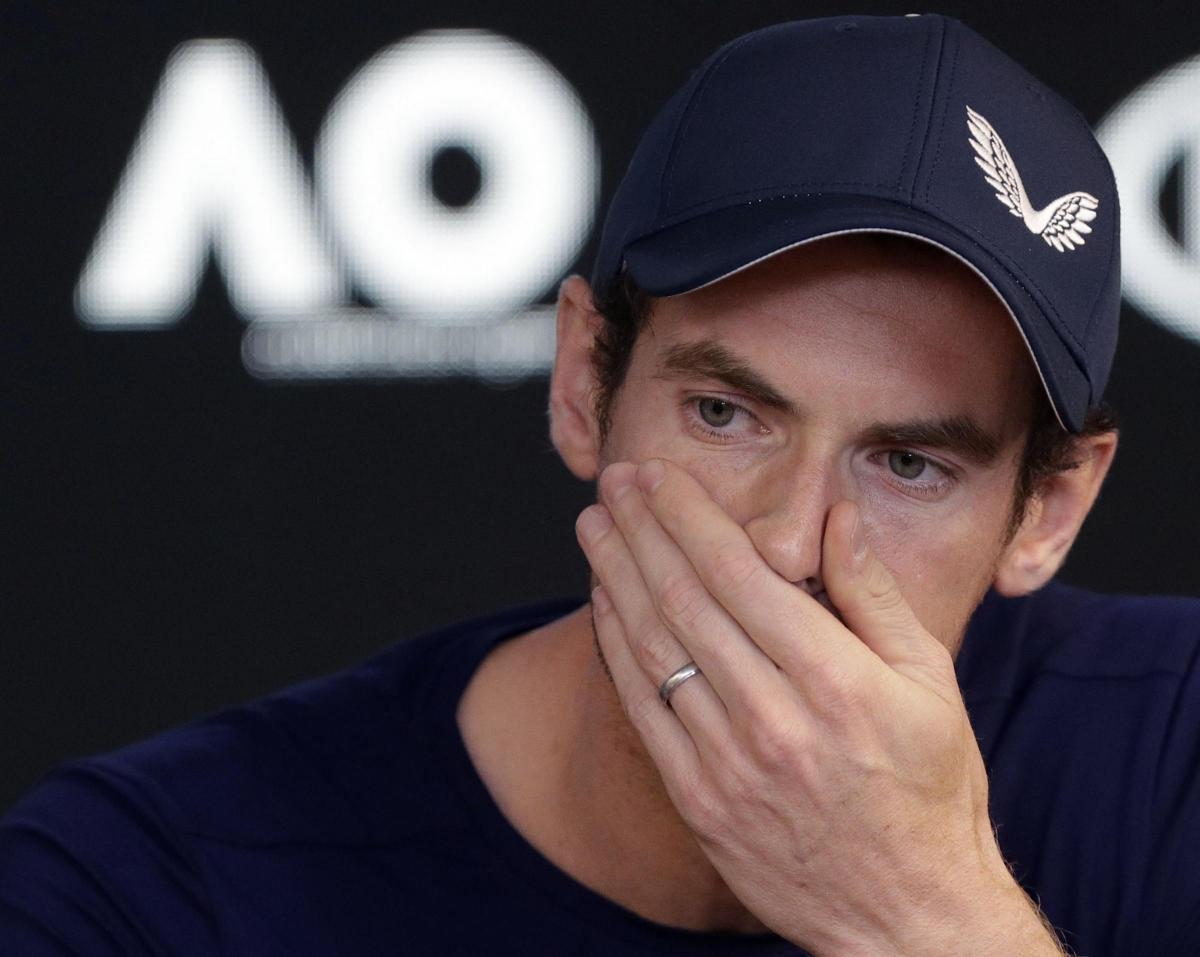

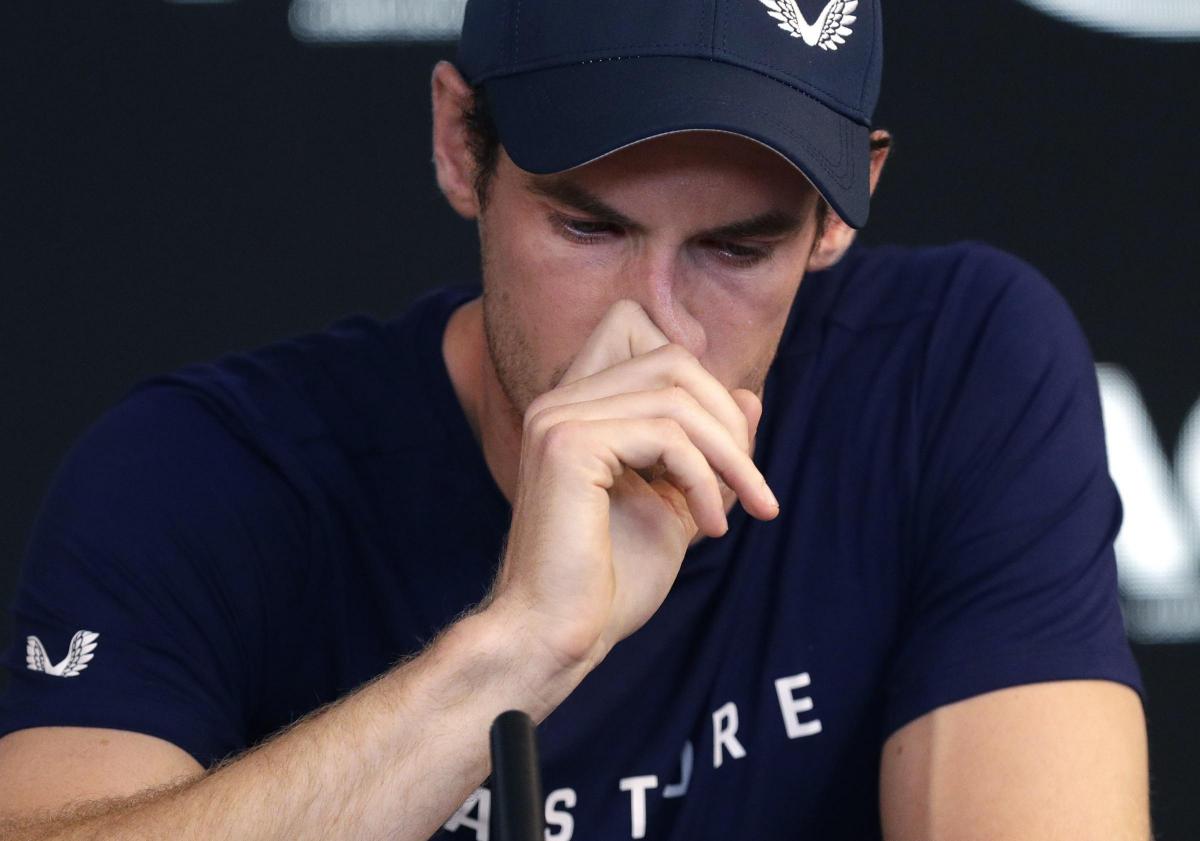

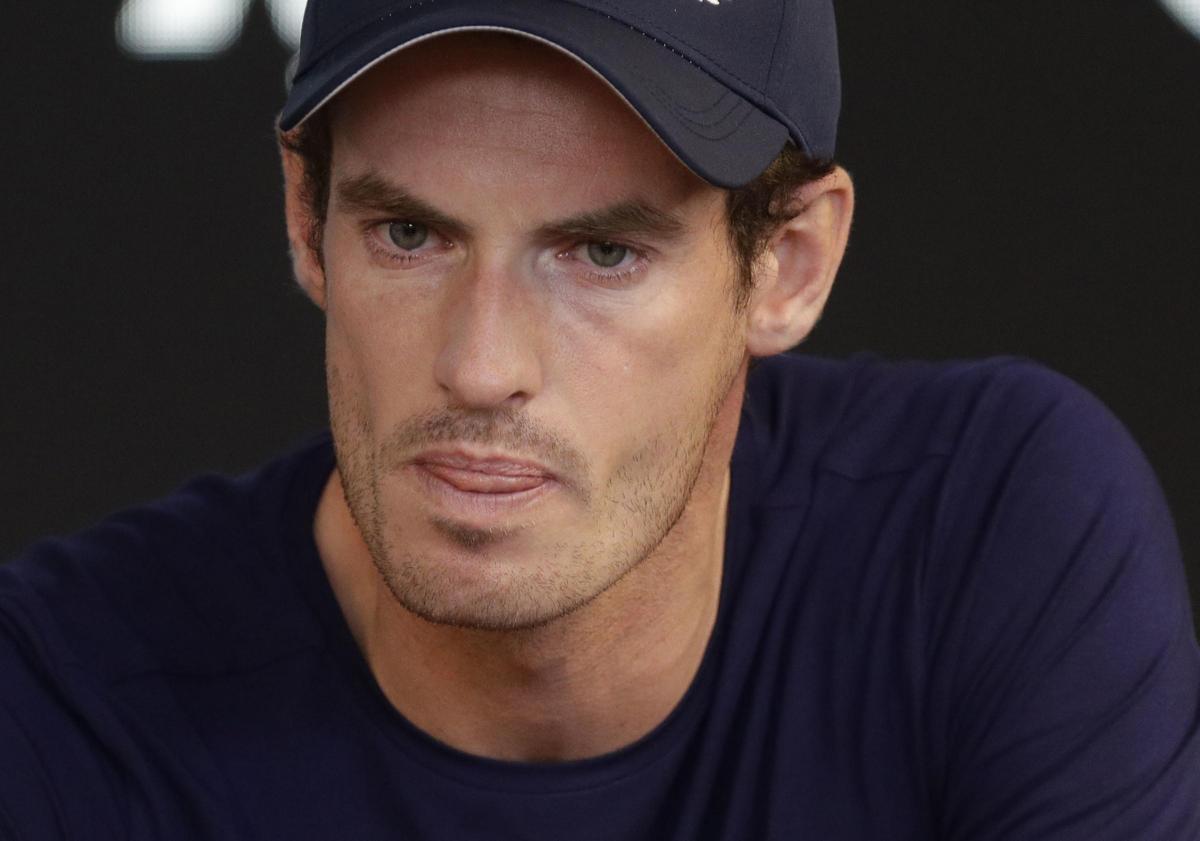

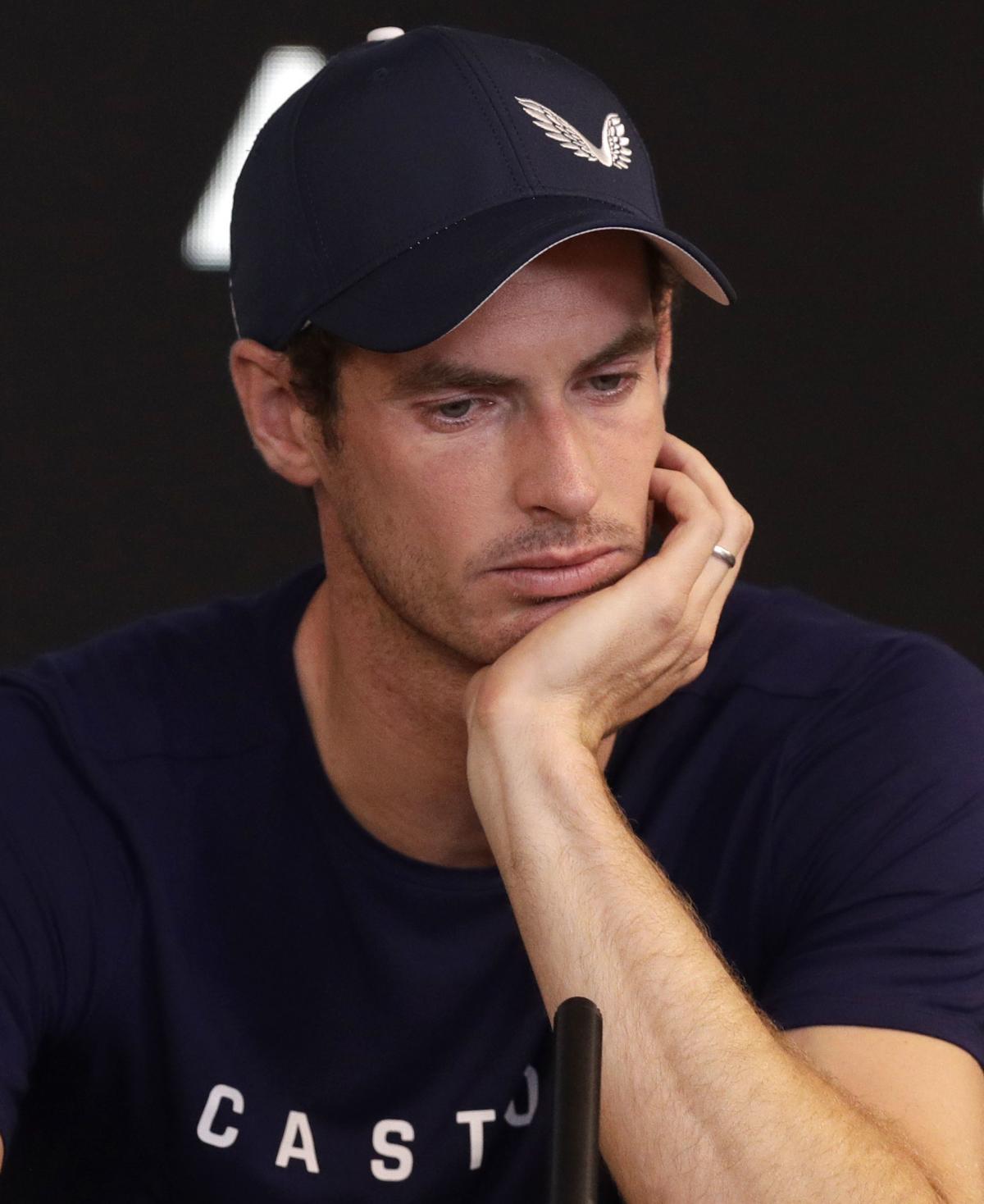

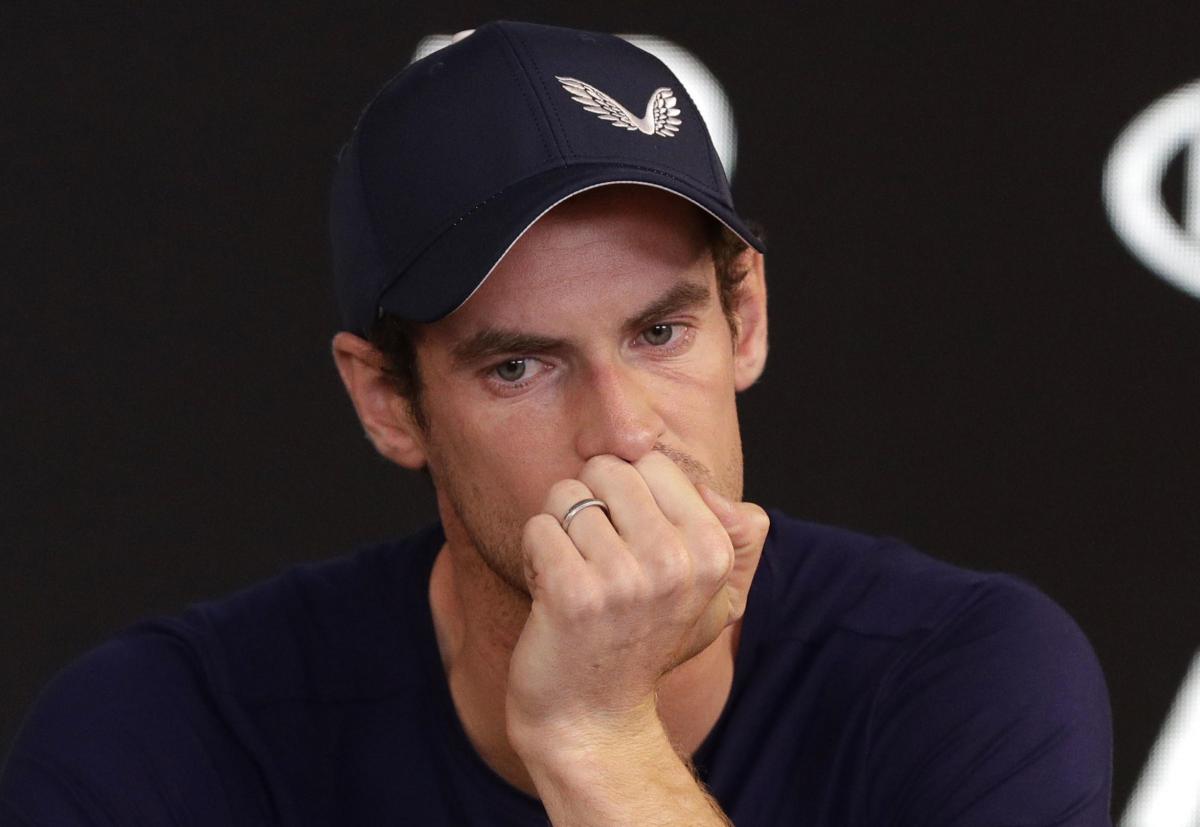

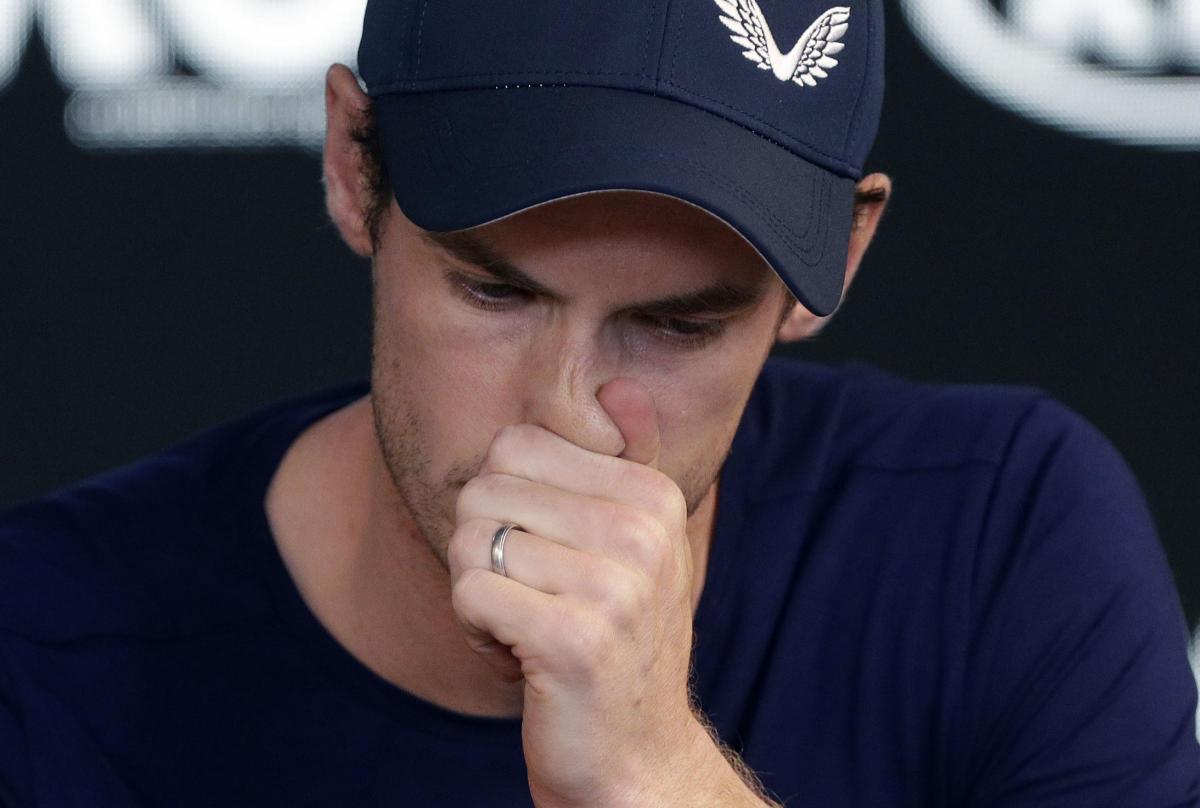

READ MORE: Emotional Andy Murray breaks down as he announces retirement from tennis

It is hugely disappointing to see the 31-year-old’s career ended prematurely by a hip condition after he finally emerged from the immense shadow of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic to make it to world number one.

But the Scot can look back at a career that delivered the biggest prizes – three grand slam titles, two Olympic gold medals and one of the most remarkable seasons in Davis Cup history to earn Britain an unlikely triumph.

Grouped together with Federer, Nadal and Djokovic as the ‘big four’, never quite on a par with them but there to be shot at by everyone else, Murray never complained about his lot.

He simply did what marked him out since his junior days, dedicated his life to wringing every last drop out of his talent.

Murray had the perfect motivation as a child growing up in Dunblane – wanting to beat his brother Jamie, who is only 15 months older – and his competitive spirit did not always make for a happy household.

Scotland is still very much home even if he has not lived there permanently for more than half his life, and it is a source of immense pride that to many Dunblane is now known as the birthplace of champions rather than for the tragedy that claimed the lives of 16 of the Murray brothers’ fellow primary school pupils.

Murray played many different sports as a child, excelling at football – his maternal grandfather was a professional player – and tennis, where being on court allowed him to spend time with his mother Judy, who was forging a successful career as a tennis coach.

Andy Murray celebrates his victory in the boys’ US Open with his mum Judy on his arrival back in Scotland (PA)

Andy Murray celebrates his victory in the boys’ US Open with his mum Judy on his arrival back in Scotland (PA)

By his early teens, Murray had established himself as one of the best young players in Europe, and a conversation with rival Nadal, who could count on former world number one Carlos Moya as a practice partner, led the Scot to broaden his horizons.

Murray headed off to train in Barcelona before making his first big mark on the global stage by winning the US Open junior title at the age of 17.

Shy, unkempt and with no desire to be a celebrity, Murray on the court stood out for the variety in his game, his tennis brain, his speed and, most of all, his tenacity.

Andy Murray hugs his mum Judy after winning his Men’s Final match against Switzerland’s Roger Federer at Wimbledon (Andrew Milligan/PA)

Andy Murray hugs his mum Judy after winning his Men’s Final match against Switzerland’s Roger Federer at Wimbledon (Andrew Milligan/PA)

Murray matches were not always pretty, although he could be spectacular as well as dogged, but he will be remembered most of all for his sheer determination to find a way to win.

If there was a criticism, it was that Murray seemed to have too many options and his default setting was to rely on his remarkable defensive and physical abilities. Would he still be playing if he had not put his body through quite so much punishment?

Ivan Lendl, under whom Murray won all his biggest individual titles, was the only coach able to consistently ramp up his charge’s aggression, while tempering the Scot’s tendency to allow negativity to overwhelm him.

Coach Ivan Lendl worked with Murray twice during his career (Mike Egerton/PA)

Coach Ivan Lendl worked with Murray twice during his career (Mike Egerton/PA)

It was no surprise Murray struggled to keep believing when always standing in his way were three of the all-time greats. Four times he lost in slam finals, twice to Djokovic and twice to Federer, before finally breaking his duck in appropriately gruelling fashion against Djokovic at the US Open in 2012.

The following summer came his career-defining moment when he ended Britain’s 77-year wait for a male singles champion at Wimbledon, adding a second title three years later then writing his own piece of history by becoming the first tennis player to win back-to-back Olympic gold medals in singles.

In the autumn of 2016, with his rivals at last showing some weakness, Murray surged thrillingly to the top of the rankings, clinching the number one spot by winning the ATP Finals in London.

Tour Finals – Day Eight – The O2">Andy Murray poses with the Championship trophy after winning the ATP Finals (Adam Davy/PA)

Tour Finals – Day Eight – The O2">Andy Murray poses with the Championship trophy after winning the ATP Finals (Adam Davy/PA)

What seemed like it might be the start of the Murray era turned out instead to be a glorious swansong. Barely six months later, the first signs of his hip problem emerged and, despite surgery and an extensive rehabilitation and reconditioning programme, there has been no way back to the top.

Perhaps even more important than his achievements on the court, the understated Murray emerged as one of the sport’s great trend-setters.

First there was Murray’s realisation in his early twenties that, rather than just employing a coach, having a team of people around him would help him reach his peak physically and mentally.

Andy Murray feels the pain of an injury at the ATP Finals (Anthony Devlin/PA)

Andy Murray feels the pain of an injury at the ATP Finals (Anthony Devlin/PA)

Then, with a grand slam title still tantalisingly elusive, he reached out to a former great in Lendl, establishing the trend of the super coach. When their partnership came to an end, Murray broke more ground by hiring Amelie Mauresmo, who became the most high-profile female coach in tennis.

Most top sportsmen would rather not stick their head above the parapet but, once he became comfortable in the limelight, Murray swam against the tide, speaking out forcefully on issues like equality and doping.

He also embraced his role as the figurehead of British tennis, actively supporting and encouraging those emerging in his wake. They could not have bigger shoes to fill.

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here