ON THE night Rudolf Hess crash-landed his plane in Eaglesham, a midwife was delivering a baby on a nearby farm.

As Baillieston nurse Catherine Nicol cared for the mother and newborn, all three were startled by a sudden knock at the door.

“It was the Home Guard,” explains Catherine’s nephew, Chris McChesney. “They held her at gunpoint until her identity could be confirmed.

“That night, because Hitler’s right hand man had landed in Scotland, everything was up in the air and anyone working outside their normal area was considered a potential spy. It must have been terrifying for her, but she was a strong woman. She had survived much worse.”

Chris, who is now 87, came along to our recent Thanks for the Memories event at Baillieston Library.

Through our regular library drop-in events, which have now taken place all over the city, and our letters page and email banks, we are compiling a fantastic archive of stories and pictures, all dedicated to the city we love.

If you would like to share your stories and photos of old Glasgow and its people, email ann.fotheringham@heraldandtimes.co.uk or write to Ann Fotheringham, Evening Times, 200 Renfield Street, Glasgow G2 3QB and share your photos and stories. Don’t forget to include a contact telephone number or email address.

Read more: Forgotten photo sparks memories of Glasgow's past

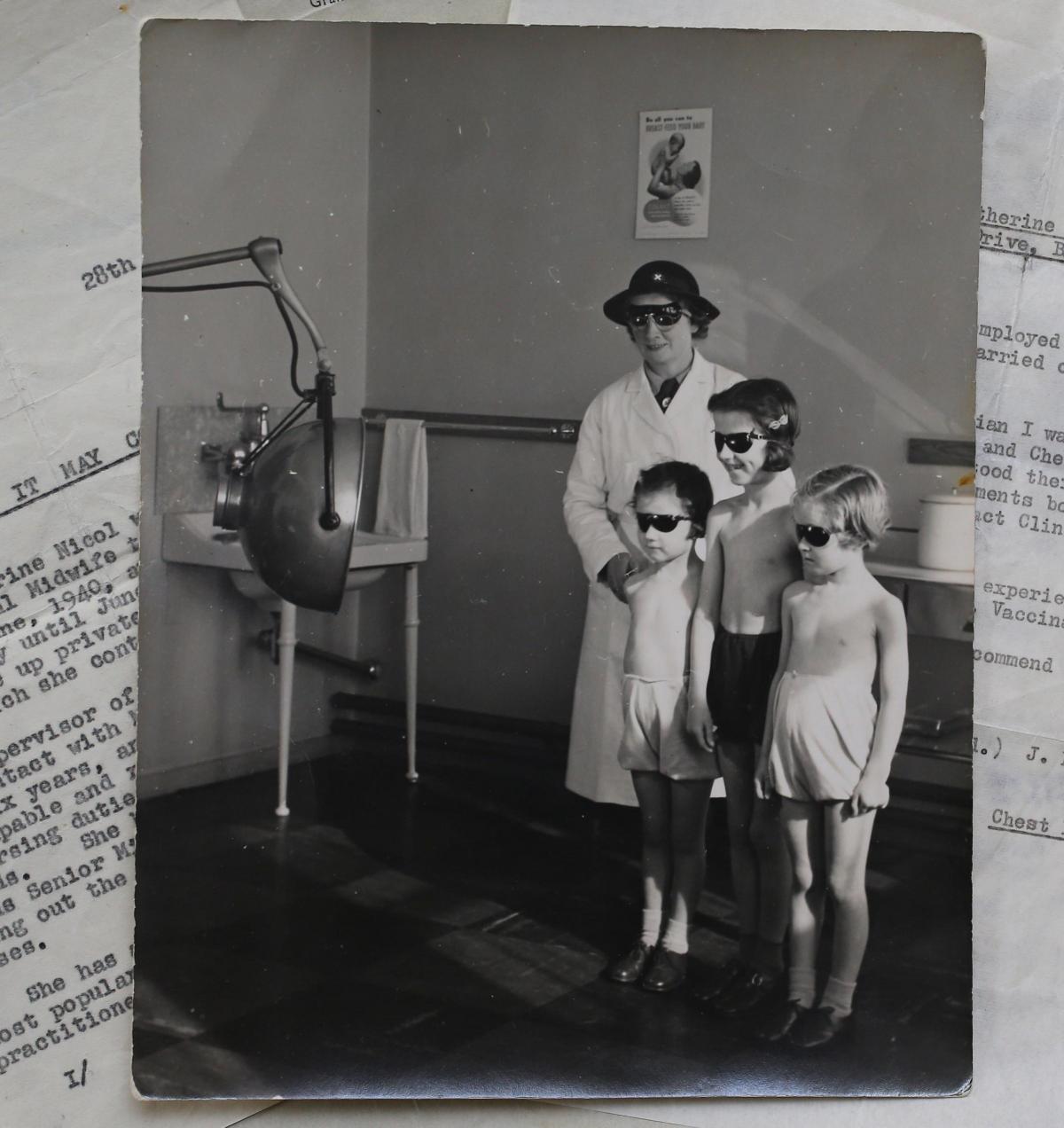

Chris’s aunt Catherine was born and brought up in Baillieston’s Douglas Drive. She suffered from a string of childhood illnesses, including diphtheria, measles, whooping cough and scarlet fever., which meant long spells in Glasgow’s fever hospital, The Belvidere.

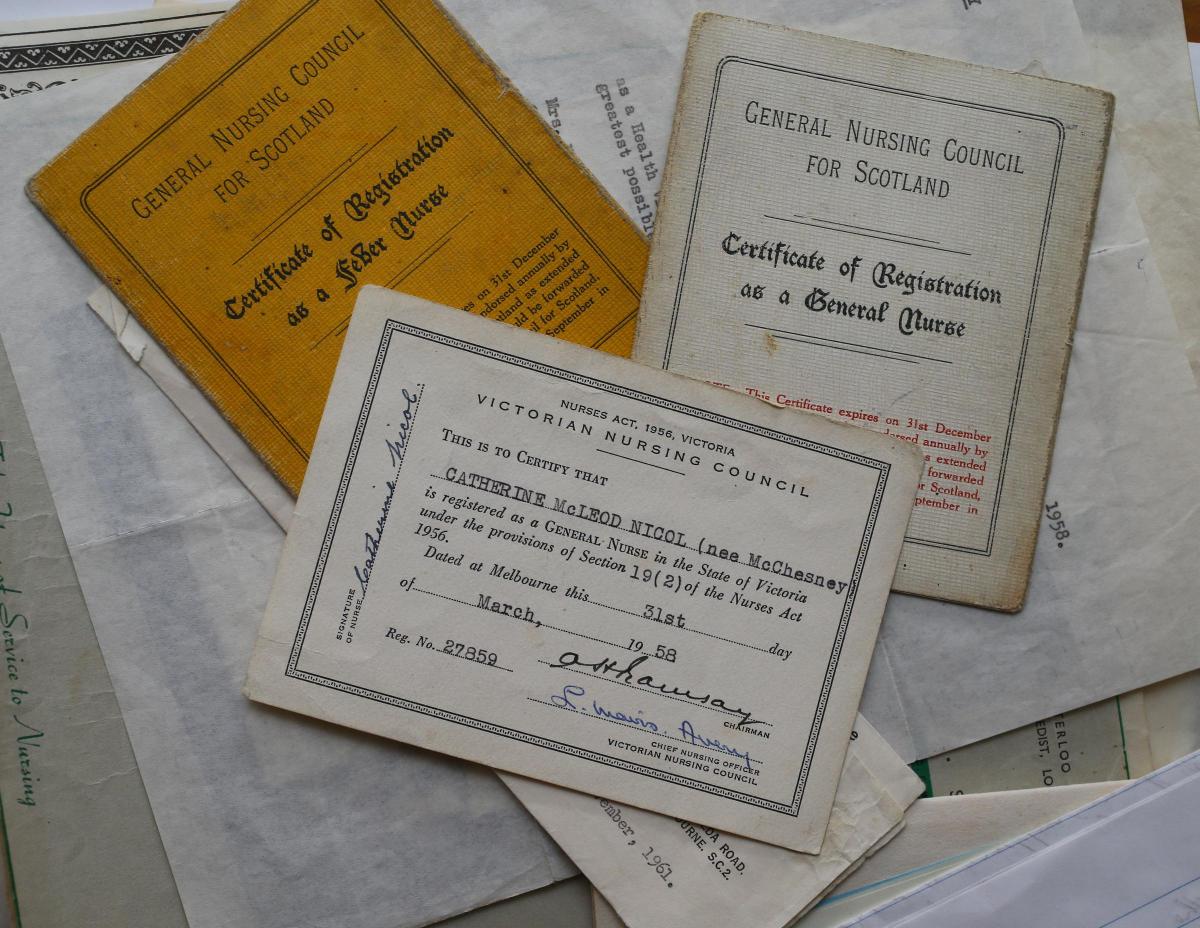

Perhaps because of the care she experienced there, Catherine decided to become a ‘fevers’ nurse, and after long years of training at Rottenrow and the Victoria Hospitals, she completed her qualifications.

“She couldn’t have known it, but she was to play a very important role at the Belvidere,” says Chris, who has kept his aunt’s nursing records and old newspaper clippings which reveal her fascinating history.

“During a smallpox outbreak, my aunt volunteered to help out and look after the victims at the fever hospital. She had to live there, in a specially built compound, in quarantine for eight months.”

“They couldn’t leave until the threat of the illness had completely passed,” says Chris.

“They all had to hand over their clothes which were burned. They were all hosed down, and their hair was cut, before they could go home.”

Catherine went on to train as a midwife, and the night she passed her final exams, she went out to celebrate at the annual dance.

“It was here she met my uncle Archie,” smiles Chris. “He was a great artist, and painted many a portrait of his wife.

“I loved them both a great deal.”

Read more: Happy times in Glasgow's east end

As a wartime nurse, Catherine had her fair share of drama, with many women going into labour in the air raid shelters.

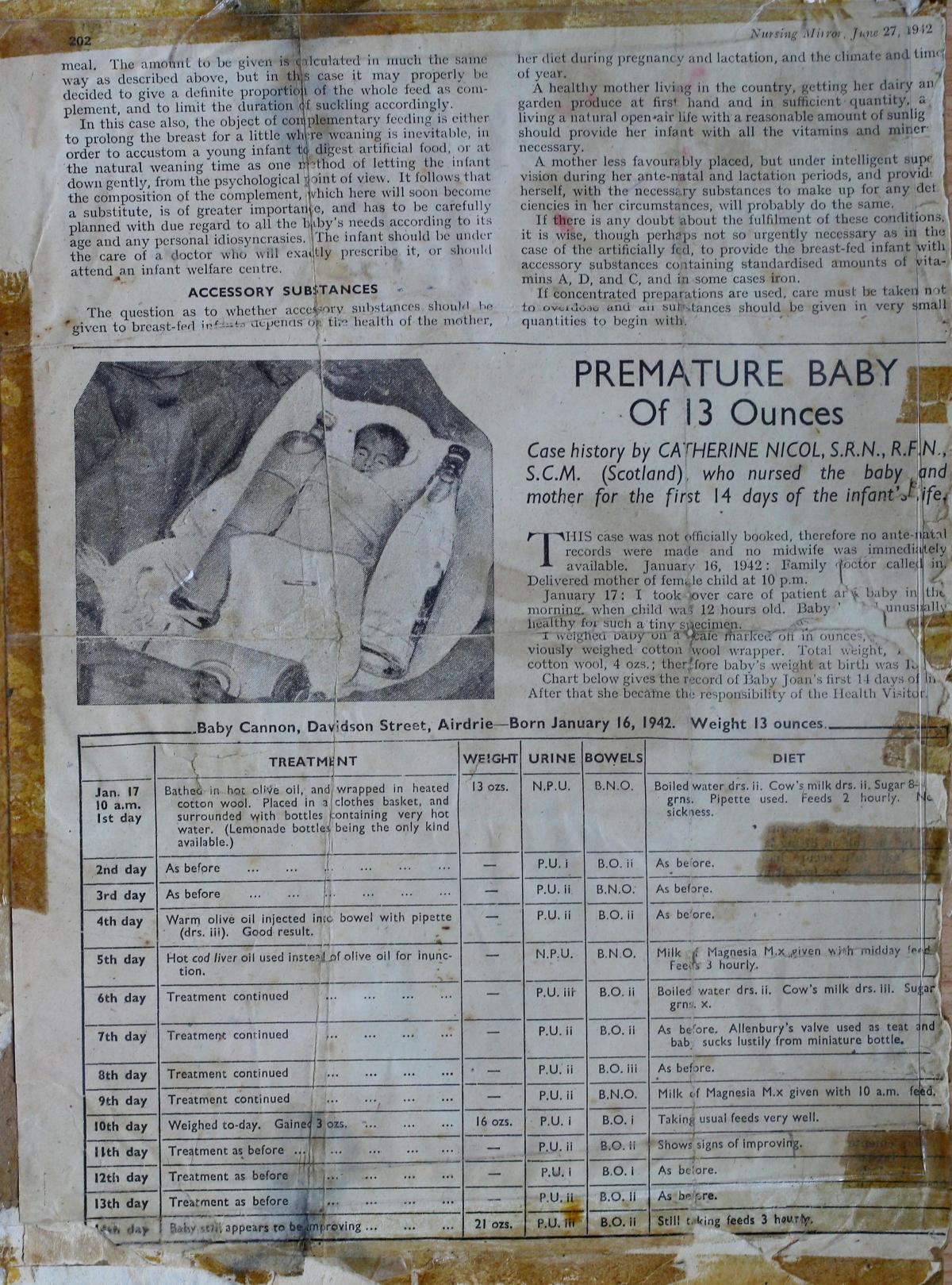

One wintry night in 1942, Catherine was called to a premature birth.

Blizzards and snowdrifts delayed her arrival, so by the time she and the doctor got to the house, the baby was already on her way.

“The doctor had all but given up as the baby was so premature,” says Chris. “But Catherine wouldn’t give up. She heated up some olive oil and massaged it into the little baby’s skin, fed her some milk every hour and laid her in a basket near the fire.

“She stayed all night through the storm, feeding her hourly.”

By the next morning, the story of this miracle baby had spread and the press was keen to speak to the nurse who had delivered the ‘Wizard of Oz’, a reference to the child’s weight – she was just 13 ounces.

Chris adds: “Catherine kept them all out, though, as she knew baby Joan was still very frail.”

Sadly, the little girl died around a year later, after contracting leukaemia and pneumonia. A story in the Nursing Mirror tells the tale, and Chris has held on to a copy to this day.

“It was even mentioned in the Lancet, this baby which weighed no more than a wee bottle of Irn Bru,” he says.

Catherine and Archie eventually emigrated to Australia, to live in the Victoria seaside resort of Rye.

“I missed them a lot,” says Chris. “I missed the cuddles my aunt would give me, when she’d laugh and say she’d squeeze me like toothpaste in a tube.

“She was a smashing person, a good person who always wanted to do her duty and help people. My uncle was talented and patient, a man whose wisdom always drew respect.”

Archie Nicol wrote a poem for his wife, which Chris has treasured since both his aunt and uncle died in Australia several years ago. It ends: “For Catherine, my own true love, I’ll ever be enthralled/I’ll sign my name, with all my love, your husband Archibald.”

“It’s a wonderful tribute to her, and it shows what a strong woman she was,” smiles Chris, whose own family – wife Senga and sons Christopher and Robin – also made Baillieston their home. The couple have seven grandchildren, aged between 10 and 18, who love hearing their grandfather’s stories of old Baillieston.

“History isn’t always about big battles and Royal families, it’s about local people and places too, and I love that,” adds Chris.

“My aunt and uncle are a part of that history and I’m proud of them both.”

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel