BARLINNIE’S imposing wooden gates loomed over five-year-old Johnny Steele, the weathered grain where notices confirming prisoner hangings were once nailed were all that stood between him and Glasgow’s most fearsome characters.

Inside was his dad Andy, safebreaker, robber and gangster, expert with gelignite and with a habit of landing inside Barlinnie, doing time, savouring his release with a party, and quite soon after landing back in.

“It was my first experience of Barlinnie,” remembers Johnny. “Those big wooden gates left an awful impression on a young mind. They were like something from a nightmare, they were intimidating. But that’s why they were that size – to scare you.”

Cut into the huge gates was a small door. On the small door was a tiny peephole, through which the wardens eyed up Johnny and his mum. “We were visiting, and they were barking out orders at us. You don’t forget that.”

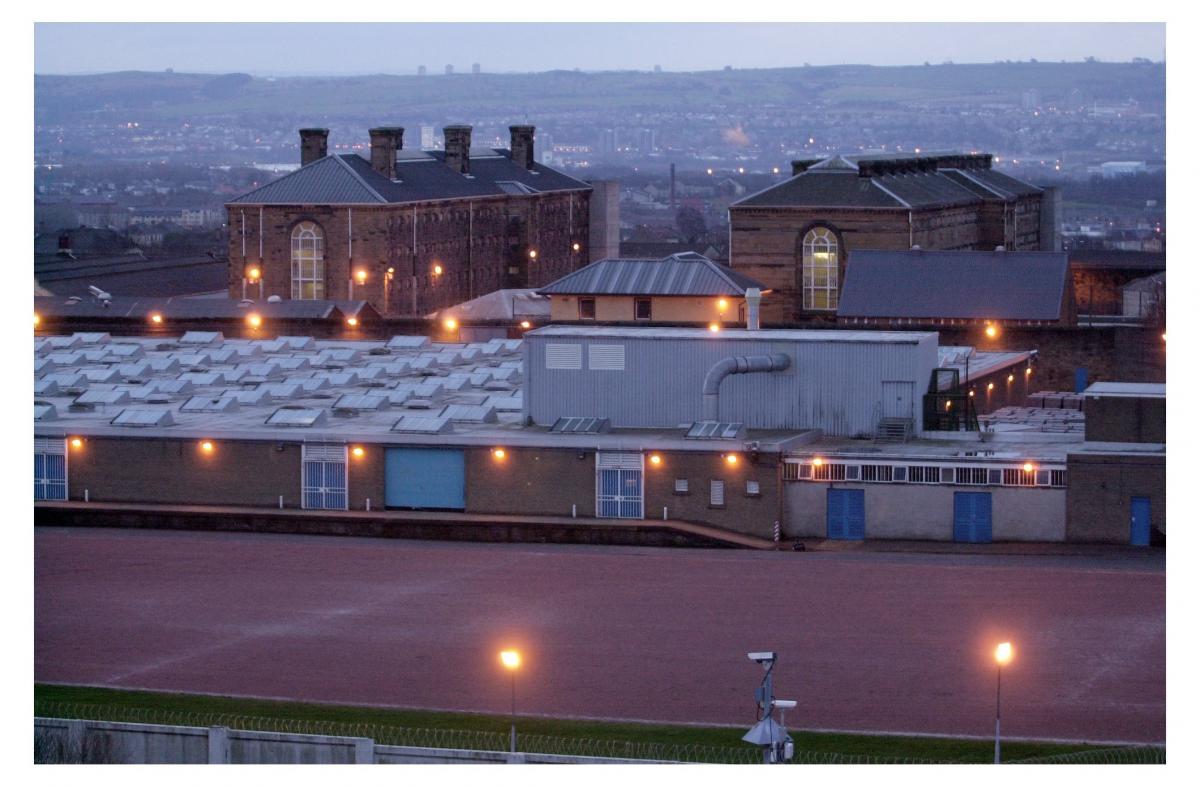

It was the early 1960s and Barlinnie, built in 1882 to outrage that thieves, killers, rapists and conmen should be granted the comforts of a gleaming sandstone ‘big hoose’, was already a withered and blackened 80-year-old relic.

By the time thieving and violence saw the 16-year-old ‘Johnnyboy’ Steele follow most of his male relatives into its dilapidated cells, lags like his dad – raised in Glasgow’s slums and more tolerant of the grim conditions – were being replaced by an angry generation prepared to riot to have their voices heard.

READ MORE:

Care worker struck off for abuse“There’s not a single prisoner who hasn’t sat inside Barlinnie and thought about how to escape,” says Johnny, one of the few to breach its walls when he scaled a shaft then abseiled 90ft to a drying green below. “It’s part of being in there. You are always looking for a way out.”

Notorious for overcrowding and a slopping out system that only ended in 2005, infamous for its violence, ground-breaking Special Unit with controversial art therapy, convicted killer Jimmy Boyle’s dirty protest and its D Hall ‘hanging shed’, Barlinnie’s daunting walls and blunt chimney pots have carved a formidable sight on the east end skyline for 137 years.

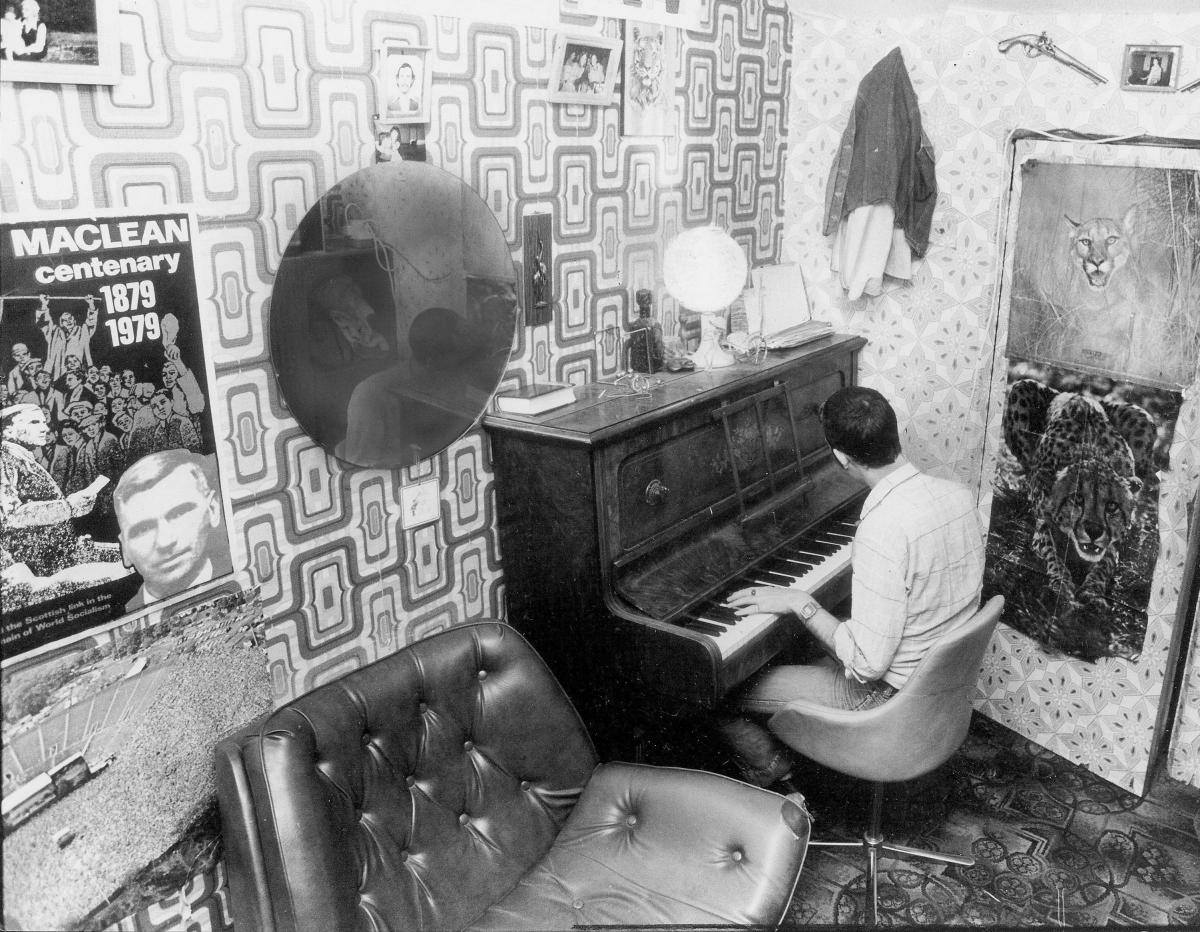

Down the years it has held fathers, brothers and cousins from notorious gangland families, footballer Duncan Ferguson – jailed for 44 days for assaulting fellow player – Dragons’ Den tycoon Duncan Bannatyne sent down for failing to pay a £10 fine, and socialist John Maclean, who feared his prison food was spiked with tranquilizers.

But like an old lag counting down the days to release, Barlinnie has now entered its final stretch.

The Scottish Prison Service has begun moves to take over the site of Provan Gas Works, off Royston Road, with plans for a 1200 capacity replacement prison likely to be lodged by the end of summer. Expected to cost around £100 million, the new HMP Glasgow will consign Barlinnie to the history books.

Built on land bought from the Barlinnie Farm Estate for £9750, Barlinnie prison was something of a country retreat for inmates from awful city slums where crime was a way of life.

It offered Victorian-age work ethics with access to education and books. The new A Hall prisoners were put to work baking and building, making shoes and mattresses, outside the quarry gave others the harsher task of breaking stone to help build B, C and D Halls.

But Glasgow crime was so rife and the judicial system so unforgiving that Barlinnie was soon bursting at the seams. By 1897 a quickly constructed E Hall took capacity to 900 but it still wasn’t enough - and hasn’t been ever since.

READ MORE:

Sexual health clinics in deprived areas closeBarlinnie already had a grim reputation when D Hall’s ‘Hanging Shed’ gallows opened in the mid-1940s. The execution cell was the last place 10 prisoners saw before being hanged and their bodies placed on a mortuary slab in a chamber below.

Some, including notorious multiple murderer Peter Manuel, never left Barlinnie’s grounds. The graves now raise the uncomfortable issue of exhuming their remains and finding a new location for burial.

For Johnny, whose escape bids contributed to him being dubbed ‘one of the most punished prisoners in the history of the British penal system’, 1980s Barlinnie was a powder-keg just waiting to blow.

“It was unpredictable, there was always a lot of stabbings. There’d be slashings with homemade shanks made from toothbrushes and running battles,” he says.

“In my father’s day, the attitude was just get through the sentence, ‘yes sir, no sir’, and get out the door. But my generation was saying ‘f*ck this, get us out of here’.”

Former priest Willy Slavin, Barlinnie chaplain from 1982 to 1992, also remembers walking through the same wooden door for the first time. Inside, he says, were “disgraceful” conditions.

“What do I remember from that first time? Dirt,” he says. “I came from a post in Bangladesh, but Barlinnie was worse for your health than Bangladesh. At least there you could do your best to survive, in Barlinnie you were subjected to the regime.

“People coming in were used to having a shower every day, but in Barlinnie they could only shower once a week. There were pots of poo in their cells. These were young people from a different world, prison needed to go along with that.”

Today Barlinnie is said to be Western Europe’s biggest single dispenser of methadone, handing out over 8700 litres every year. But he remembers an Alcoholics Anonymous request for prisoner support groups being met by stony silence.

“There were men with severe mental health problems. The medical centre seemed to hand out two paracetamols for a headache and eight for a broken leg,” adds Willy, who writes about Barlinnie in his book, Life is Not a Long Quiet River.

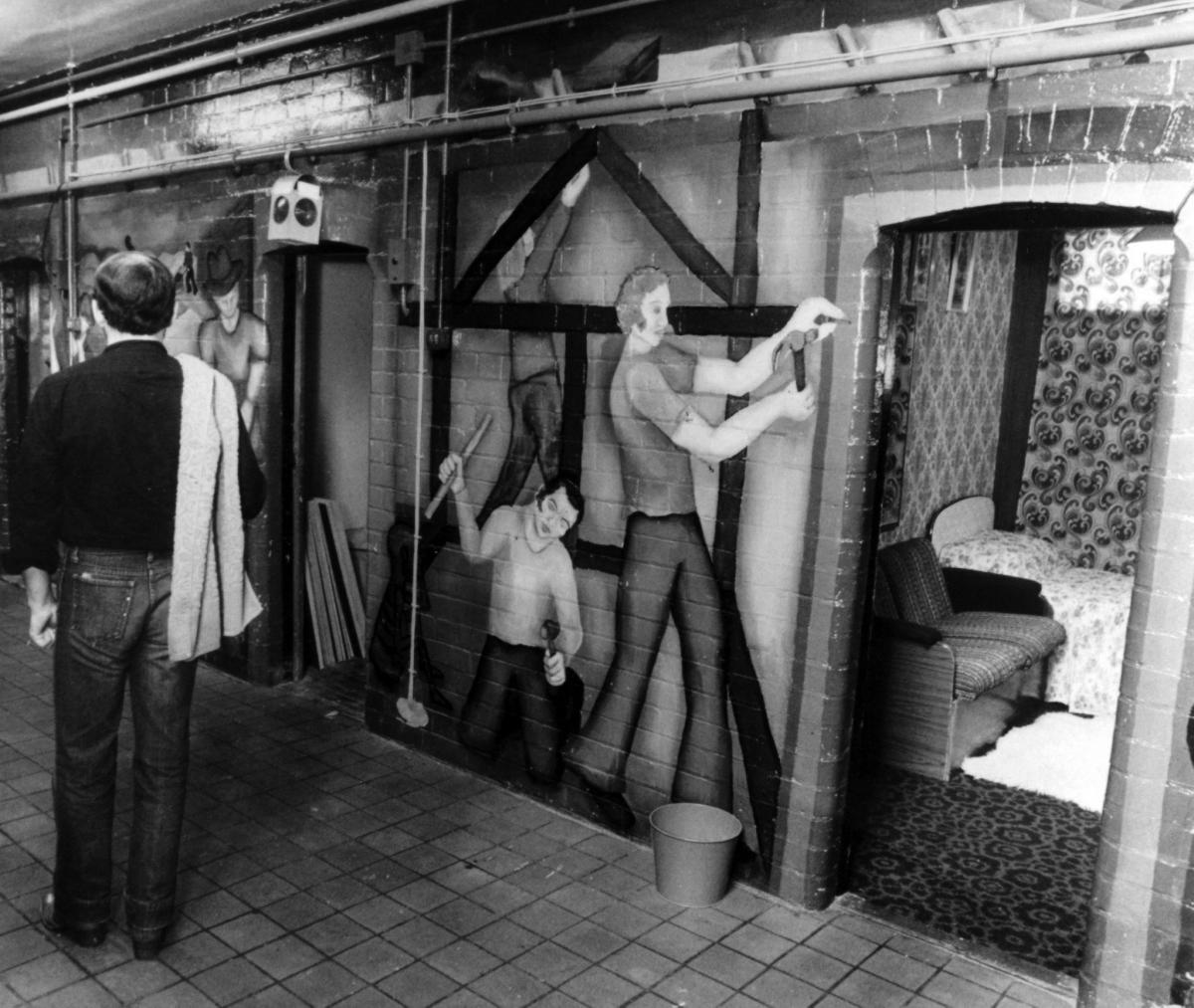

While most prisoners languished in miserable conditions, Barlinnie’s Special Unit took some of the most notorious and introduced them to an experimental regime of art, poetry and literature.

Johnny joined them but was initially so confused by its laid-back approach that he craved the ‘security’ of his old cell. Some, like convicted killers Jimmy Boyle and Hugh Collins thrived and became respected artists.

Calls for reform grew increasing loud. A wave of prison riots across the country arrived at Barlinnie in 1987, sparking Scotland’s longest prison siege. Inmates ripped apart its Victorian halls, others climbed on the roof with five staff hostages and posters claiming brutality.

Intended as a ‘short stay’ prison, Barlinnie housed perhaps the world’s most famous prisoner of the time, Lockerbie bomb convict Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi, for four years. For an hour in 2002, South African President Nelson Mandela sat with him, later emerging to tell how abuse from fellow prisoners left the Libyan enduring “psychological persecution”.

Today, Barlinnie handles 20 per cent of Scotland’s prisoners. Even visiting time is a logistical nightmare of around 7300 visitors every month, including around 1100 children.

But while still crippled by overcrowding – with an official capacity of just over 1000, it currently houses 1400 men – Barlinnie’s tough regime has been replaced by a more enlightened approach.

In his 2011 inspection of the prison, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons Hugh Monro noted: “Barlinnie is well led and the staff have a good understanding of what they are required to do. Staff embrace change and are not afraid to lead the way in innovative practice.”

With the end in sight, it’s been suggested Barlinnie could be reborn as social housing or upmarket flats; a world away from rows of 6ft by 11ft cells and slopping out.

For Johnny, whose uncle perished in a fire in his Barlinnie cell and whose brother Joe was wrongly convicted of Glasgow’s Ice Cream War murders, it’s hard to imagine no more Bar-L.

READ MORE TOP GLASGOW STORIES“But it would make a fascinating museum,” he adds. It’s full of history.”

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel