SO many ways to tell. Over the last few days I’ve been reading a range of new graphic memoirs that show just how vibrant and diverse those ways can be; both in form - everything from scratchy pen to collage and painting – and content – ranging from straight reportage to fable, from family memoirs to sexual violence and civil war.

All of them in their own way are seeking to pin personal experience to the page, render it visible, comprehensible. They are repositories of memory, explorations – investigations, even - of personal stories, and, on occasion, acts of witness.

Let’s start with Travis Dandro’s King of King Court (Drawn and Quarterly). This is a brick of a book, filled with scratchily intimate, closely drawn imagery (you do worry for the cartoonist’s eyes at points).

King of King Court offers a double time frame; the cartoonist as a young kid in 1980, and the cartoonist as a teenager 10 years later. In both he is dealing with a mother who is unhappy with and ultimately separated from his stepdad, while still attracted to Dandro’s father, who in turn lifts weights, steals money and ultimately has issues with drugs and violence. It is a book about how decisions taken by your parents impact on the life you find yourself leading.

It’s also a book that grows on you. At first, I was a little irritated by the way Dandro shifted from a child’s eye view to an adult’s in the early part of the book. Partly that was because he was so good at the former and I thought he could have used it to frame the latter too. Because at its best the book catches that sense of childish close attention; to the landscape, to the animals that surround us and to the emotional weather that the boy he was doesn’t really understand.

But as we move into the 1990s section what is striking is how Dandro continually deepens and complicates our understanding of the lives we are being shown. He manages to offer empathy to all the people in his life, even the ones he hates.

There are moments of high tension, melodrama even. But some lives are melodramatic. Dandro knows this.

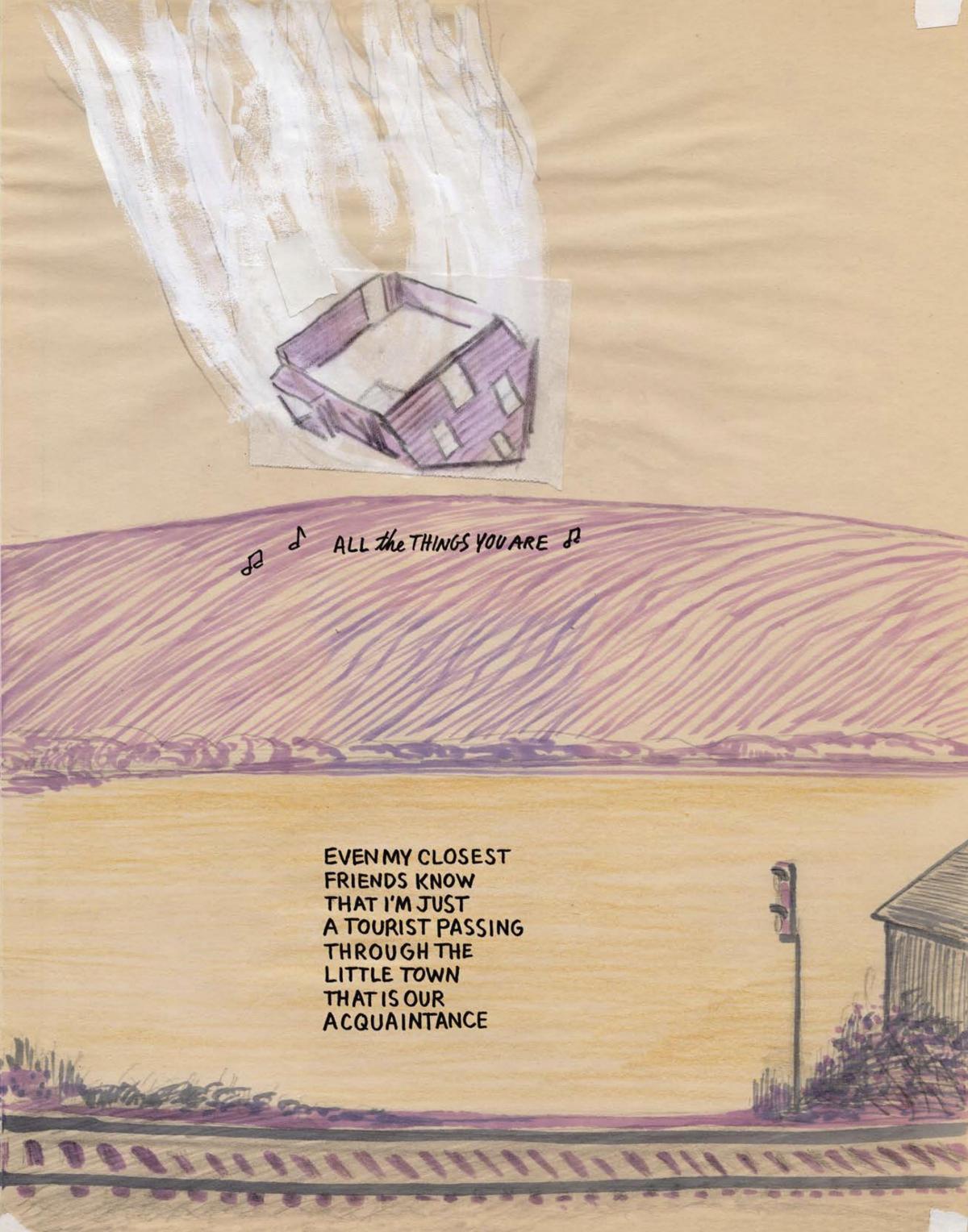

In Frank Santoro’s Pittsburgh (New York Review Comics) the violence is more internal than external. Santoro uses collage and marker pens to tell the story of his parents who have separated and now work in the same building and yet never speak to each other.

It’s the story of their lives in the 1960s, and, like Dandro’s, how the influence of their own parents had an impact on their children, and their children’s children (in this case Santoro).

It’s set in working-class Pittsburgh. While Santoro’s dad was off serving in Vietnam. Santoro’s mum seemed to get on with her boyfriend’s parents than her own. Without that, Santoro junior might never have been born.

Santoro’s grandmother on his dad’s side – Mary – was Scottish, originally from Dalkeith. She met her husband during the war when he was in the UK as a GI. She became a war bride, a Scottish Protestant transplanted to Catholic Pittsburgh.

When Santoro’s grandmother on his mum’s side threatened to send her daughter to California (in an effort to break up her relationship with his GI dad), it was Mary who intervened.

Santoro is attempting here to tell the story of how he came to be, about the threads and connections that bound two people together long enough to create another human being, and how easily those threads can be broken, and how far back the reasons for that break can go.

Santoro’s art has a rough, vivid tactility that veers between highly detailed and highly sketchy. It reflects a narrative that recognises the gaps in people’s stories. We can see what people look like, but can we ever fully know their story?

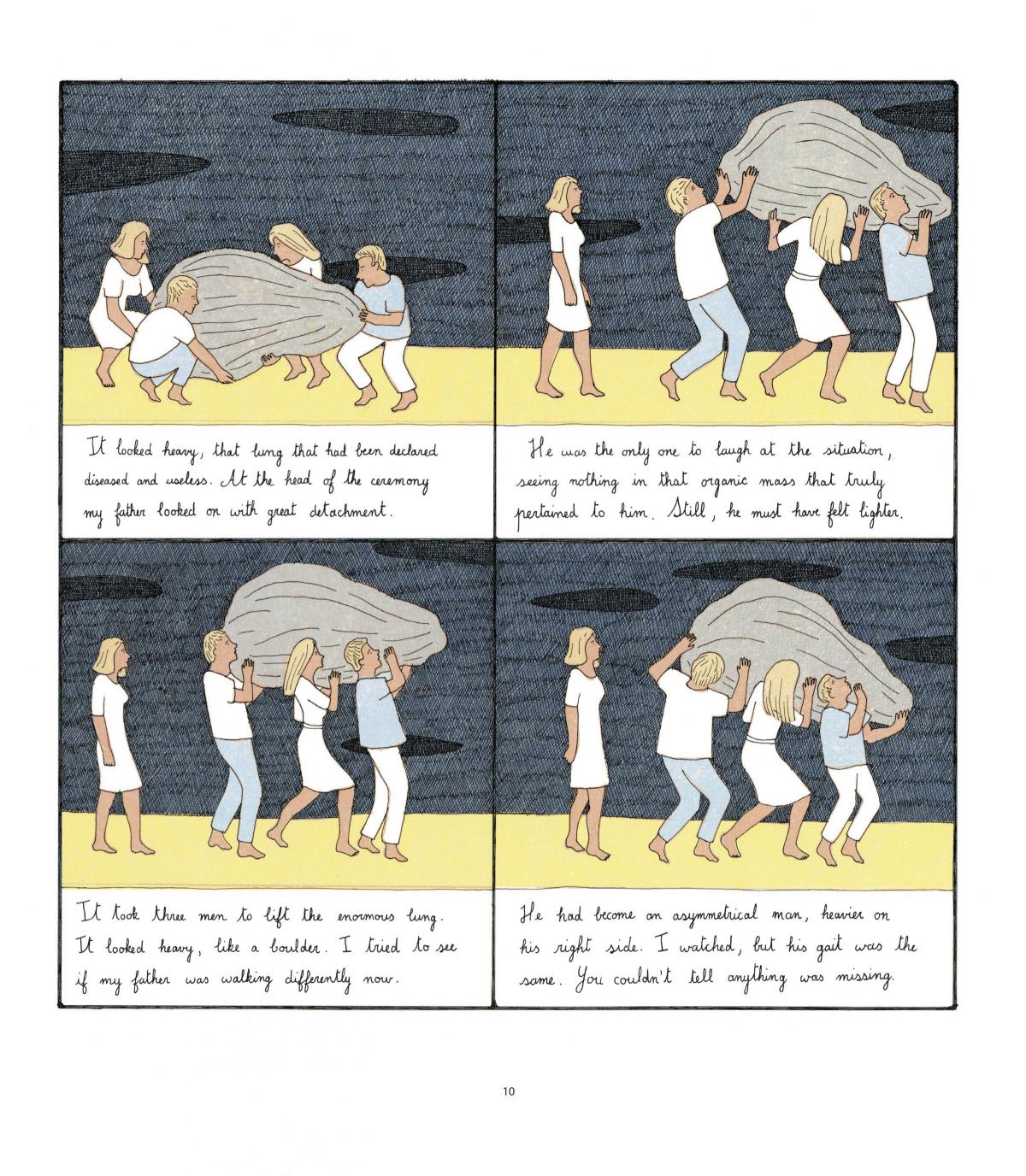

Marion Fayolle’s The Tenderness of Stones (New York Review Comics) takes a step back from memoir and embraces fable. “We buried one of dad’s lungs,” the female narrator begins and the book follows the surrealist erasure of said “dad” over more than 130 pages.

It’s a book about illness, about presence and absence, told coolly from a distance in finely drawn, beautifully coloured illustration. It reroutes painful experience, reflects and refracts it back to us in strange, angular myth that horrifies all the more because of the calm detachment of its telling.

And like Santoro’s Pittsburgh it’s another example of good publishing. Both books are beautifully designed and handsomely put together. Fine reminders of just how thrilling the bookishness of books can be.

Not that all graphic memoirs need to wear their Sunday best, though. Hot Comb, by Ebony Flowers, is a thing of wobbly lines and cartoonish exaggeration that still offers a fresh, punchy insight into the everyday lives of African-American girls and women. It’s about black hair and black music and black identity. Or race, class and perms.

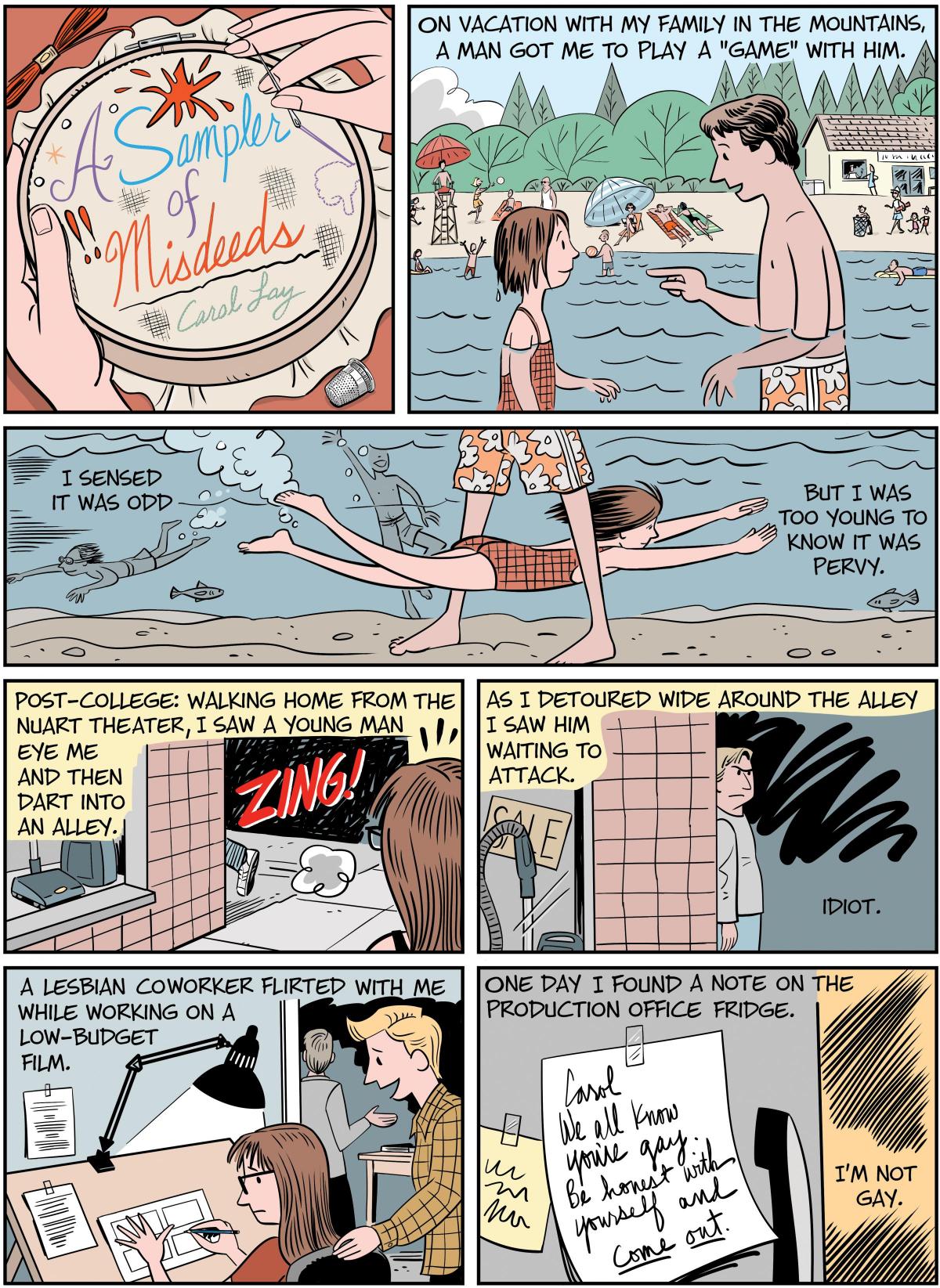

Ebony Flowers also turns up in Drawing Power (Abrams Comic Arts), an anthology that aims to tell “women’s stories of sexual violence, harassment and survival”. Edited by Diane Noomin, and featuring short, punchy strips by more than 60 cartoonists (including the likes of Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Emil Ferris, Lee Marrs and Sarah Lightman), it’s, inevitably, an angry book.

Men don’t come out of it well (with the exception, maybe, of Paul Kossoff. (The late lead guitarist of Free turns up and is kind in Corinne Pearlman’s All Right Now. Nearly every other man in these stories is frankly, an arse.

I can tell you all about the range and quality of the cartooning here, but it feels less important than the message. What’s most striking is how many of these women find humour in their material. A case, perhaps, of if you don’t laugh …

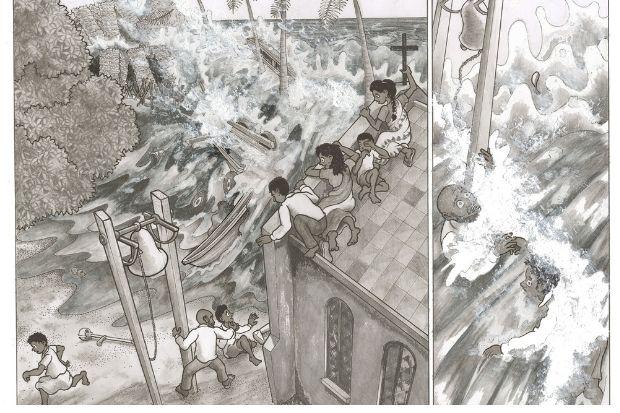

Finally, the act of witness. Vanni (New Internationalist), by Benjamin Dix and Lindsay Pollock tells the stories of two Sri Lankan families in the early years of this century who are battered by, first, the 2004 tsunami and then the resurgence of civil war between the Sri Lankan government and the Tamil Tigers.

It’s the story of civilians in wartime; how vulnerable and expendable they are. Reading it I initially worried that Pollock’s art might be too Disney in its attractiveness to truly reflect the horrors of what happened to the people he was drawing, but in fact it simply gives it even greater impact as the story unfolds and the two families reel from horror to horror, caught in the crossfire between the Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tigers. Here is the true cost of war; grief, PTSD, a stripping away of all the norms and comforts of a life. How do we stay human in that situation? That is the question Vanni asks. The answers are not easy.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here