Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn

Brett Anderson

Little, Brown, £18.99

Review by Teddy Jamieson

THE Gourock Bay Hotel. 1992. Suede, “the best new band in Britain” according to the Melody Maker (a popular weekly music newspaper of the time, Milord), have just finished playing their libidinous, circling song Pantomime Horse in front of a small, surly crowd in a back room. As the desultory clapping dies away and the band ready themselves to launch into their next song, a gruff Glaswegian voice breaks the silence with a notably withering review. “You effete southern wankers!”

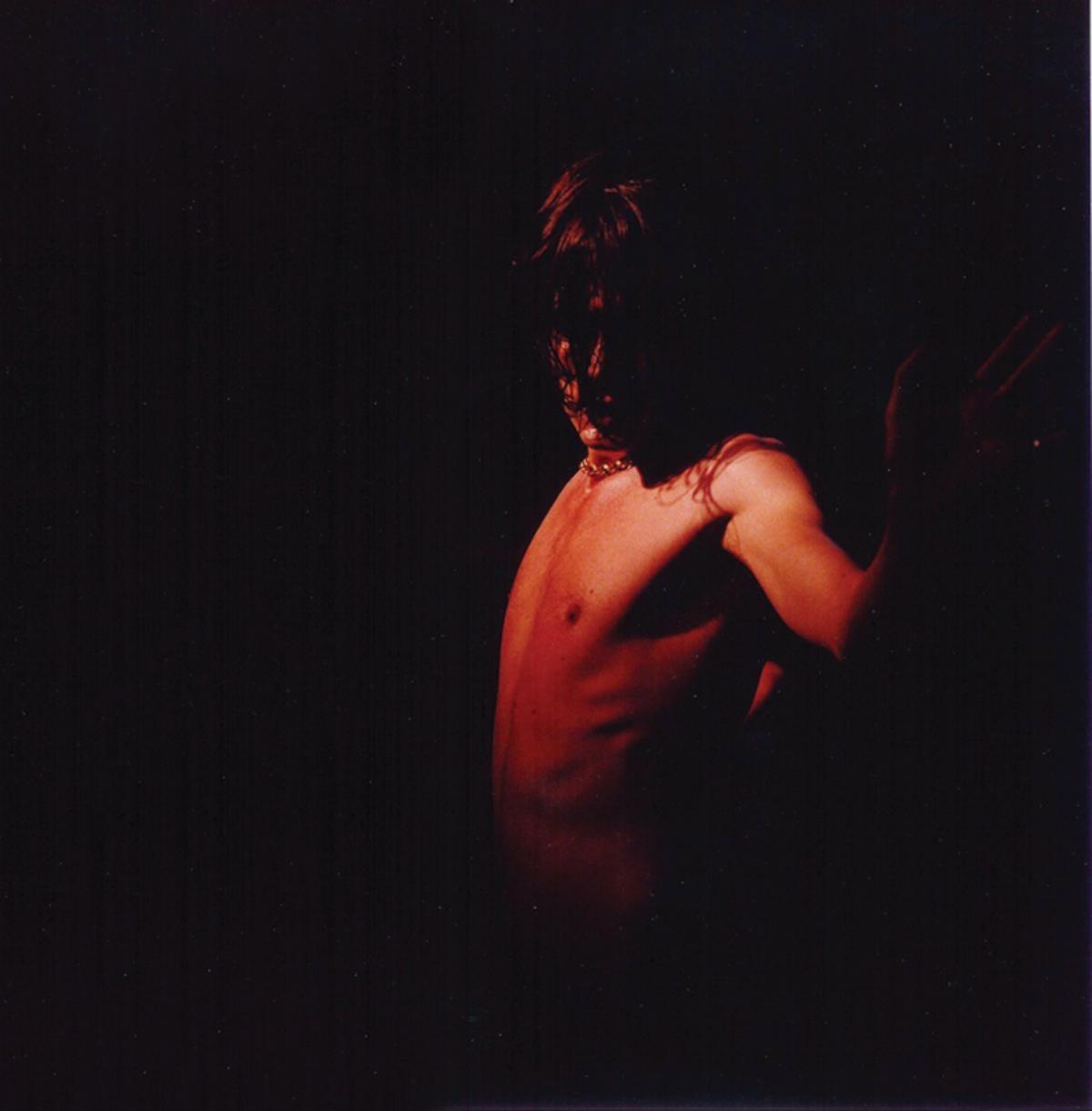

It’s a moment remembered with some amusement by Suede’s front man Brett Anderson in his new memoir, Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn. In truth, Suede were always a Marmite band. Most of that was down to Anderson, thanks to his penchant for wearing women’s blouses, being playfully androgynous, owning a falsetto voice that irritated as many as it thrilled and his very obvious belief attitude that his band were better than anyone else’s (to be fair, an attitude that you would find in any band of the time; it was generally accepted to be part of the job description).

What some saw as effete, others however (and, yes, my hand is raised at this point) believed thrillingly transgressive. Between grunge and techno, Suede were the first glittering, narcotic vision of what would come to be called Britpop. “I’d always had a desire to pollute the mainstream with something poisonous,” Anderson writes at one point.

Others would wipe away the mascara, ditch the sexual ambiguity and become huge as a result. But for a moment in the early nineties Suede offered a vision of what a British band could be; dark, sexual, provocative, effete if you will.

In the years that followed they were both embraced and reviled by the music press, had hits, fell out, took too many drugs, lost members, made more records, toured constantly, carried on long after they really needed to, split up and then years later got back together again.

It’s a familiar story. Perhaps too familiar for Anderson. In the introduction to his first book, Coal Black Mornings, Suede’s front man defended its concentration on the pre-history of the band. “The very last thing I wanted to write was the usual 'coke and gold discs' memoir,” he wrote then.

Well, he has now. That’s exactly what Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn is; an account of Suede’s salad years and their wilting aftermath. At times it feels like he is faintly appalled that he has done so. The resulting memoir is curious. It’s both revealing and reticent. He is both very honest and also, at times, deeply evasive. The fall-out with fellow band member Bernard Butler, Suede’s musical driving force, during the making of their dark, murky, swirling masterpiece Dog Man Star, to take one example, feels like it happens offstage (partly perhaps because by the end they couldn’t bear to be in the same room at the same time).

In fact, the whole book has a hermetic sealed-in quality to it; all dust motes and drizzle and interior voice. Reading it is a bit like being inside a Suede song itself. Which is maybe a mark of the strength of Anderson’s vision. (At times, too, his prose can be rather arch and affected, but that in itself is also very Brett.)

That said, the book’s insularity is as much a strength as a weakness. For a start, it offers a corrective to the bumptious laddishness that characterises many Britpop memoirs. (Shall we call it the Gallagher option?) But then Suede always had more in common with Massive Attack and Tricky in their world view than Oasis and Blur at their most music hall.

And Anderson’s honest enough about himself, painting a picture of a young man dressed in nothing but a Moroccan robe, reading William Blake and Aleister Crowley, and taking too many chemicals. “A damaged, paranoid figure, wired and isolated, edgy and obsessed and lost within a strange fantasy landscape, a simulacrum of life.”

In a way the book’s main problem is that “coke and gold discs” issue. How do you make the familiar rise-and-fall music narrative fresh? I’m not sure Anderson totally manages it, to be honest. As he trawls through the creation of various B sides you do feel this is great for the fans but not for the general reader.

And yet there is much to cherish here. Anderson is an adroit chronicler of rented London flats. The pages reek of stale cigarette ash, rising damp and mouldy grouting. From Notting Hill to North Kensington to Paddington and on to Knightsbridge, Anderson and his best mate Alan smoke and scheme and debauch themselves across the city. At one point, reading his description of yet another nicotine-coloured flat, I found myself fantasising about pitching Channel 4 an anti-aspirational TV pilot called Bedsitterland, hosted by Anderson and, say, Marc Almond, which would celebrate the “drying, browning artichokes” and the “torn Rizla packets” rather than Eames furniture and all-mod-cons kitchens.

Anderson’s choice of interior decoration doesn’t notably improve in the wake of Suede becoming a chart band. But in every other sphere success proves an accelerant. “By this point in my career,” he writes in the wake of the band’s best-selling third album, Coming Up, “I think that my ego was, to say the least, burgeoning.”

Ego and excess. To his credit, Anderson never revels in the drugs stories here. There are no blow-by-blow nor snort-by-snort breakdowns. Suffice to say, it’s clear that it’s happening, and it seems anything but glamorous. Afternoons with the blinds drawn sums it up. This dissolution reaches a climax towards the end of the book that, thankfully, just falls short of disaster. But only just. The older Anderson now has little time for the idea that excess is an aid to creativity.

Inevitably, the book offers the singer’s own nuanced take on pop and success. He is still in love with the former but found the latter disorientating. “In pop music everyone becomes a cartoon,” Anderson suggests. The problem comes when that cartoon persona develops a separate life to the person it’s attached to. Especially when the person is complicit in its creation.

“Years of poverty and struggle and failure had made me hungry for any scraps of success that were thrown my way,” Anderson admits, “and in my frenzy to feed I think I was often far too willing to indulge their silly fantasies and wear the costume that was so carefully stitched for me despite the fact that it increasingly seemed ill-fitting.”

Inevitably it becomes too heavy to wear anymore. Afternoons With The Blinds Drawn ends backstage at the Graham Norton Show with Anderson finally admitting: “I can’t do this anymore,” to his fellow bandmates and friends.

All bands, Anderson suggests, follow the same career arc. The same points are plotted along the way, he suggests, “like the Stations of the Cross; struggle, excess, disintegration and if you’re lucky – enlightenment.”

This is a book written from a position of enlightenment. That enlightenment might also be the reason that Anderson doesn’t ever fully pull back the curtain on his younger self. He is protecting the innocent. And the guilty. It’s a mark of decency; a mark which his younger, callow, attitudinal self might not have recognised.

But we are given enough of a glimpse to hope that there might be a third volume, one that covers his solo years, his rapprochement with Bernard Butler and the records they made together as The Tears, and finally, in recent years, the rebirth of Suede which has given the band a thrillingly fierce third act. Turns out effete is the last thing they are.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here