GLASGOW’S status as the “dear green place” was strengthened by a bold programme of park building during the Victorian period and one of the jewels in the crown was Queen’s Park.

The expansion of the city and increase in population density during the 19th century (particularly south of the river) led to demands for more common outdoor spaces. One key driver was the cholera epidemic of the 1840s, which prompted the council to take a more interventionist approach than had it had done previously.

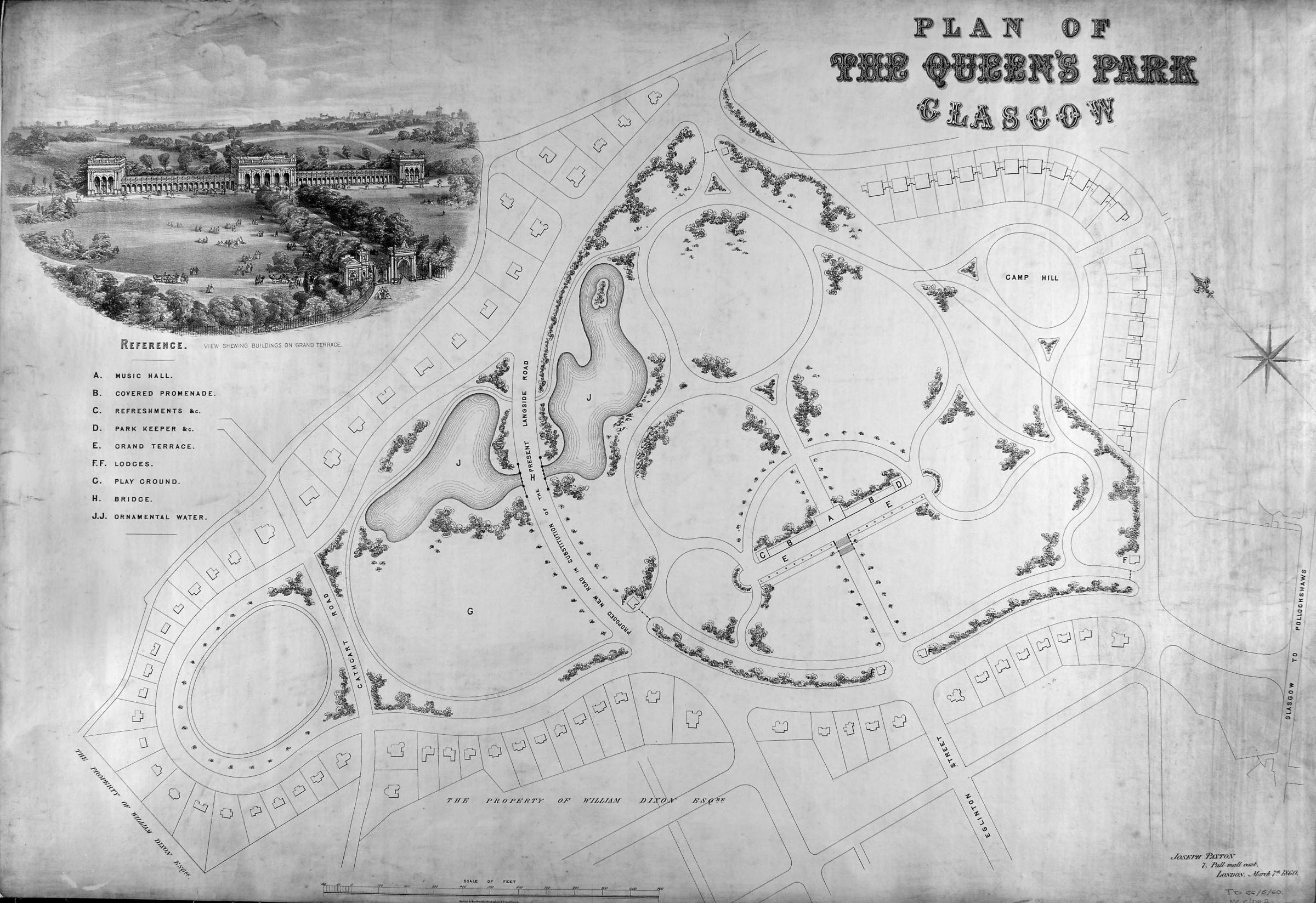

It bought a patch of land some two miles south of the city boundary and started planning the new “South Side Park”. Councillors appointed Sir Joseph Paxton - the pre-eminent planner of the day who had just designed the Crystal Palace in London - to draft the plan.

Plan of Queens Park Glasgow. Pic: Glasgow City Archives

Paxton’s ambitious design is held in the City Archives. As well as a large ornamental lake, it included an elaborate covered winter gardens facing Victoria Road for staging musical performances, exhibitions and displays of art. Clearly sympathetic to the Glaswegian climate, Paxton urged councillors to proceed with the covered building so that visitors could enjoy outdoor exercise and have somewhere to shelter.

This proposal was considered too extravagant and a toned-down version endorsed instead. Work commenced in 1857 and the new Queen’s Park opened in September 1862, with much of the landscaping having been carried out by the unemployed. As part of the opening ceremony, a horse chestnut tree was planted at the entrance to Wellcroft Bowling Club. This tree, with its distinctive “W” shaped trunks, still stands today.

Camphill Pond c1912. Pic: Glasgow City Archives

The park owes its name not to Queen Victoria, as some of the surrounding street names might suggest, but Mary, Queen of Scots. The Battle of Langside, at which Mary’s army was routed, took place in 1568 on the site of the park. Many streets in neighbouring Battlefield pay homage to Mary, including Dundrennan Road and Lochleven Road – respectively the names of the abbey and castle where the vanquished Queen was imprisoned.

READ MORE: Crowds flock to be part of Glasgow Times Past: City Memories

The creation of parks in Glasgow was often driven as much by commerce as improving the health and wellbeing of its residents. Green spaces increased the value of surrounding property, meaning nearby land could be sold off at a premium. In the case of Queen’s Park there was a third driver: politics. As the site lay outside the municipal boundary, its formation can be seen as a move to expand the city by demonstrating to south-siders the benefits of belonging to Glasgow.

The plan backfired initially. Residents resisted the absorption to the city until 1891, meaning they had access to the park for almost 30 years without having to pay for it.

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here