IT COULD have been horrific.

A young soldier home on leave inadvertently foiled a terrorist plot that almost blew up the Possil aqueduct.

Had it succeeded, hundreds could have died in mass drownings...

The little-known story of the Glasgow Dynamitards, as they became known, is one of many unearthed by city-born writer and journalist Thérèse Stewart for her book, Scottish Canal Crimes, Murder and Mayhem on Scotland’s Canals 1800-1950.

The Forth and Clyde Canal at Maryhill, 1937. Pic: Herald and Times

These are grisly tales, of murder and kidnapping, of infanticide and stolen corpses, all linked by the country’s canal network.

“I was doing some historical research, and the more I read, the more I discovered references to crimes that had taken place on canals,” says Thérèse, who writes as TA Stewart.

“These were stories that generated a lot of excitement and interest at the time but are barely known about now.

“The more I read, the more questions I had, so I started to research it more thoroughly and the book grew out of that.”

Glasgow crimes feature strongly in the book, which is available from Rymour Books, a Perth-based independent publisher. Over the next few weeks, Times Past will feature some of the most shocking, starting with the terrorist plot on the Forth and Clyde Canal in 1883.

Thérèse explains: “On the evening of Saturday, January 20, 1883, Adam Barr and his friends had been on a night out. The 23-year-old from Springburn had joined the Royal Artillery as a gunner.

“The group was making their way back late at night by the towpath of the Forth and Clyde Canal. As they reached the Possil Road aqueduct they spotted a suspicious-looking object – a large tin box. A woman in the group, who feared that there might be an abandoned infant inside, suggested they look inside.

Scottish Canal Crimes is available now.

“Adam put his hand inside and found a sand-like substance. He was in for a shock - as this triggered a loud bang and a fizzing noise, and a strange smell that rose up in the air.

“He could barely shout a warning to the others when there was a second explosion - louder and more powerful. They were all thrown backwards by the force of it and Adam had burns to his left hand and arm and his face was hit by flying debris. Eventually the box stopped fizzing and the sandy substance dwindled away. Adam was really puzzled - he knew all about explosives because of his job in artillery, but he had never smelled anything like this before.

“The shocked young people were treated by local police and officers seeking evidence at the aqueduct found a sawdust-like substance and a brass tube with a cap. They realised local residents had had a lucky escape. If the explosion had been worse, the aqueduct might have collapsed, releasing a deluge of water onto the streets below, perhaps causing mass drownings.

“Unbeknown to Adam and his companions there had been two other explosions in the city a short time before, so from the start the police were treating the aqueduct incident as part of a bigger plot. The first had been at Tradeston Gasworks, just after 10pm. Windows shattered and a few cottages partly collapsed, sending locals fleeing to safety. A few were sent to hospital for treatment. The second explosion had been on a railway bridge crossing Dobbie’s Loan. A shed blew open and as parts of it flew around, staff had to dodge the debris. Fortunately, no one had been in the shed at the time.

“The city authorities were nervous, so they posted guards at aqueducts, railway stations and the gasworks. Suspicions first fell onto rail workers who were striking about long working hours, but this was ruled out.

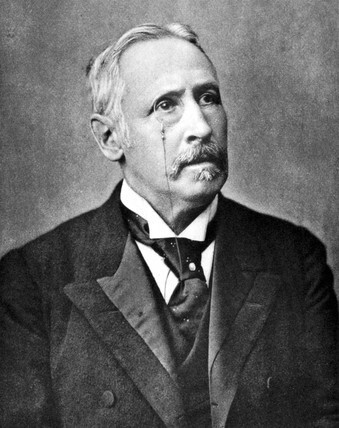

Colonel Vivian Majendie c. 1895

“Experts travelled up from London to investigate. Colonel Majendie, a leading explosives expert, identified the sand-like substance at the aqueduct as a compound used by Irish nationalists in incidents south of the border, including attempts to blow up an army barracks and the office of The Times newspaper.

“On the evening of Friday April 6, police arrested a man coming out of a pub on Garscube Road. He was an Irishman named Bernard Gallagher who had recently returned from America. He was charged with being involved in the explosions at Possil Aqueduct and the gasworks.

READ MORE: The day Maryhill schoolboys got arrested for playing footie on the street....

“In London, police swooped on his brother, Dr Thomas Gallagher and his associates. As well as being a physician, Thomas was an expert chemist. At the trial later that year, it was argued that Bernard had such serious alcohol problems he was usually far too inebriated to set up an explosion, and besides his involvement couldn’t be proved. However, his brother Thomas was seen as the ringleader and was found guilty with three other men. Their sentence was penal servitude for life.

“But the hunt wasn’t over yet. There was a second batch of arrests in September 1883 and a further group were charged with intending to destroy the aqueduct and causing the two other explosions. These men were believed to be members of an Irish ‘ribbon society’ said to have been involved with a complex bomb-making undertaking. All were found guilty, five of them given penal servitude for life. They were taken to serve their sentences south of the border. They so-called Glasgow Dynamitards were viewed as particularly dangerous individuals whose actions could have cost countless lives. As an example to others, they were kept under exceptionally grim conditions in prison.”

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here